1 Kings

Share

This resource is exclusive for PLUS Members

Upgrade now and receive:

- Ad-Free Experience: Enjoy uninterrupted access.

- Exclusive Commentaries: Dive deeper with in-depth insights.

- Advanced Study Tools: Powerful search and comparison features.

- Premium Guides & Articles: Unlock for a more comprehensive study.

Golden Calves (12:1-33). This chapter treats the watershed event in 1 Kings. King Rehoboam's refusal to rescind the oppressive forced labor and tax measures of his father, Solomon, split the kingdom. The ten tribes of Israel under Jeroboam seceded from Jerusalem, fulfilling the prophecy of Ahijah (see 11:29-39). Rehoboam attempted to reclaim his kingdom, but the prophetic word from Shemaiah prohibited him. Rehoboam's greatly reduced kingdom became known as Judah. Rehoboam's name means one who enlarges the people, but ironically he divided the people.

King Jeroboam built his military command at Shechem, an important religious and political site in Israel's history (Josh. 24). He knew that his political fortunes were tied to the religious life of the nation. He set up two golden calves at Dan and Bethel (see Hos. 8:4-6; 10:5; Amos 7:8-13). He encouraged local high places and authorized a non-Levitical priesthood. He initiated an annual feast at Bethel in the eighth month to rival the Feast of Tabernacles traditionally celebrated in the seventh month (1 Kgs. 12:25-33; see Leviticus 23:33-43). Jeroboam cried out, "Here are your gods, O Israel, who brought you out of Egypt" (1 Kgs. 12:28). These gods were patterned after the sacred bull of Egypt (see Exod. 32:4) and the calf worshiped by the Canaanites. Yet Jeroboam tied the worship of these calves to the Lord's deliverance of Israel from Egypt. If Jeroboam intended to continue the worship of the Lord, the calves were meant only as pedestals for Israel's invisible God. From the sacred writer's viewpoint these calves were signs of pagan idolatry.

Man of God (13:1-34). An unnamed prophet of the Lord delivered a message of judgment against Jeroboam's royal shrine at Bethel. He predicted that Josiah would destroy the Bethel worship site. This occurred in 621 b.c. when King Josiah of Judah initiated extensive religious reforms (2 Kgs. 23:15-17). When Jeroboam saw that he could not harm the prophet, he enticed him to stay. But the Lord had forbidden the prophet to eat or drink in the Northern Kingdom.

As the man of God left Bethel, an old prophet hoping to fellowship with him met the prophet and, using deceit, persuaded him to stay. The man of God foolishly agreed to dine with him. After the man of God left his host, a lion on the road killed him. When the old prophet discovered the body, he exclaimed, "It is the man of God who defied the word of the Lord." Ironically, the death of the man of God proved that his predictions about Bethel would "certainly come true."

Jeroboam's sinful altar was the reason for his downfall and ultimately the demise of Israel (see 14:16; 15:29; 2 Kgs. 17).

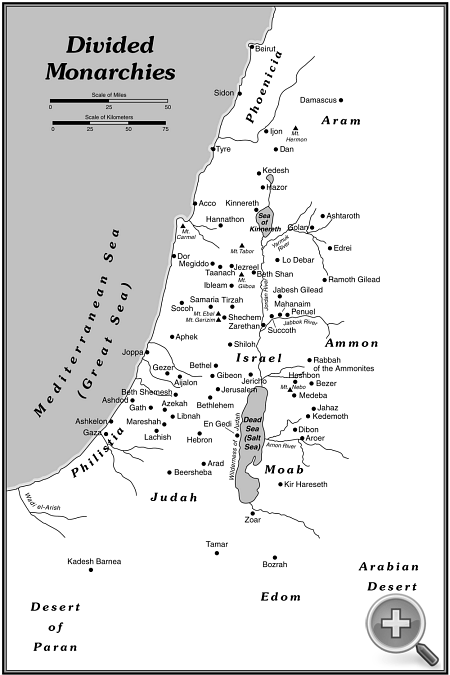

MAP: Divided Monarchies

Denouncing Jeroboam (14:1-20). Jeroboam's wife, disguised as another woman, visited Ahijah the prophet at Shiloh to learn the fate of her ailing son Abijam. The prophet was not fooled and denounced the house of her husband. He predicted the boy would die and the Lord would raise up another dynasty to cut off the progeny of Jeroboam (see 15:29). The prophet also foretold the exile of Israel. Jeroboam reigned twenty-two years (930-909 b.c.).

Chastening Rehoboam (14:21-31). Rehoboam squandered his heritage through spiritual apostasy. His reign was as wicked as Jeroboam's with its high places and male cult prostitutes. Although Judah was preserved because of the promise to David, the Lord in anger punished Rehoboam for his wickedness. He was afflicted by Shishak (Shoshenq), who was the founder of Egypt's Twenty-second Dynasty (945-924). An account of his wars is inscribed on the wall of the temple at Karnak. Rehoboam paid him handsomely from the gold accumulated by Solomon. Rehoboam reigned for seventeen years (930-913 b.c.).

Abijah and Asa 15:1-24). Abijah's three-year reign was evil, but God sustained his throne as a "lamp" in Jerusalem for the sake of David.

Asa, however, received a good report from the sacred historian. His reign of forty-one years (910-869 b.c.) included reforms, though he did not remove the high places. During Asa's reign, Baasha of Israel built a fortress near Jerusalem at Ramah. Asa entered a treaty with Ben-Hadad, king of Aram (Syria), who attacked Israel. Baasha left Ramah and dismantled the fortress.

Nadab of Israel (15:25-32). Nadab succeeded his father Jeroboam but reigned only two years (909-908 b.c.). He did evil in the sight of the Lord like his father. Baasha assassinated Nadab and killed the whole household of Jeroboam, fulfilling the prediction of Ahijah (see 14:10-11,14).

Baasha and Elah (15:33-16:14). The dynasty of Baasha was founded by assassination and ended in the same manner. The prophet Jehu condemned the evil of Baasha and foretold the demise of his house. He reigned for twenty-four years (908-886 b.c.) and was succeeded by his son Elah (886-885 b.c.). In a drunken stupor he was assassinated by Zimri, a court official. Zimri executed the whole family of Baasha just as Jehu had prophesied.

Zimri's Seven Days (16:15-20). Zimri's reign, the Third "Dynasty," had the distinction of being the shortest in the history of Israel. He ruled for seven days before he committed suicide in the flames of his palace. His demise was plotted by General Omri, who led an expedition against Zimri for his murder of King Elah.

The House of Omri (16:21-28). Omri defeated Tibni, a rival to the throne, and founded the Fourth Dynasty in Israel. His reign was only twelve years (885-874 b.c.). His fame was so great that a hundred years after his death the nation Israel was still called the "house of Omri." Omri had close ties with the Phoenicians, even marrying his son Ahab to the Tyrian princess Jezebel. Omri moved the capital of Israel from Tirzah to Samaria. There the kings of Israel ruled until its destruction by the Assyrians in 722 b.c.

Ahab and Jezebel (16:29-34). Ahab and Jezebel reigned for twenty-two years (874-853 b.c.). Together they attempted to make Israel a pagan nation devoted to Baal and Asherah, the deities of the Sidonians. Ahab erected an idol of Baal in Samaria and built an image of the Canaanite goddess Asherah. The sacred historian was unimpressed with Ahab's many political accomplishments. Twice he evaluated Ahab's rule as more evil than all his predecessors.

During the reign of Ahab, a man named Hiel, who was from the sinful city of Bethel, rebuilt the city of Jericho. His sons died under the curse Joshua pronounced upon anyone who restored the city (Josh. 6:26). The author included this account to show that the Lord's judgment on sin is certain. Ahab too would suffer for his sins.

The Elijah cycle of stories departs from the stereotyped reporting of the kings in chapters 12-16. The stories of the prophet Elijah show that the makers of Israel's history were not the kings but the prophets who dramatically shaped the future of each royal house.

Elijah's ministry occurred during Israel's greatest religious crisis under Ahab and Ahaziah (1 Kgs. 22:51-2 Kgs. 1:18). Ahab's reign declined because of wars with Aram and his theft of Naboth's vineyard.

Trouble for Ahab (17:1-24). Elijah the Tishbite is introduced in the book suddenly as an envoy from the Lord. He proclaimed to Ahab a great drought which would end only when Elijah gave the word (see Jas. 5:17-18). The drought was a refutation of Ahab's Baalism because Baal was reputed to be the god of rain and vegetation. This showed that the Lord was the true Lord of nature.

During the three-year drought, Elijah dwelt with a widow and her son in Zare-phath of Phoenicia, the native land of Jezebel, where Baal was worshiped. The drought had spread to Phoenicia, and the Lord used the prophet to provide food to this family. When the woman's son became ill and stopped breathing, Elijah prayed three times, and the Lord answered by raising up the boy. Because God did these miracles in Phoenicia, this showed that the Lord was the God of all nations and that Baal did not exist.

Choosing the Real King (18:1-46). For three years Ahab and his servant Obadiah desperately sought the elusive Elijah. Elijah unexpectedly met Obadiah in the road and promised Obadiah that he would see the king. When Ahab met the prophet, he called Elijah the "troubler of Israel." Yet it was Ahab who caused Israel's distress. Elijah proposed a contest with the prophets of Baal and Asherah at Mount Carmel.

The contest was for the benefit of the people to learn who truly ruled Israel—the Baals of Ahab and Jezebel or the Lord God of their fathers. The contest consisted of preparing a sacrifice and praying for the deity to prove his existence by answering with fire from heaven. Baal was reputed to be the god of storm and therefore should at least have been able to bring down fire (lightning).

The prophets of Baal prayed all morning, but there was no answer. Elijah ridiculed their pagan theology. Then in ecstatic frenzy they frantically slashed themselves to draw their god's attention (see Lev. 19:28; Deut. 14:1), but there was no answer. At the evening hour of sacrifice, it was Elijah's turn. He rebuilt the altar of the Lord and called upon God, identifying Him as the "God of Abraham, Isaac and Israel." Fire fell and the people exclaimed, "The Lord—he is God!" The people executed the evil prophets.

God also sent a great rainstorm to end the drought. The storm rained upon Ahab as he hurried to Jezreel. The hand of the Lord empowered Elijah to run ahead of Ahab's chariot to the city.

Elijah Hides at Horeb (19:1-21). Elijah's victory, however, turned into fear and depression. Surprisingly, Jezebel was not intimidated by Ahab's report of Elijah's deeds. She vowed to kill the prophet, who ran again but this time away from Jezebel to the desert. In despair the prophet prayed to die (see Num. 11:11-15; Job 6:8-9; Jon. 4:8). The angel of the Lord strengthened him with food, and he journeyed forty days and nights to a cave at Mount Horeb. It was upon the same Mount Horeb, another name for Mount Sinai, that the Lord had revealed Himself to Moses (see Exod. 3; 19).

Elijah complained that the Israelites had abandoned God and that he was the last prophet of the Lord. But Elijah was mistaken. God brought in succession a great wind, an earthquake, and a fire to ravage the mountain. But the prophet did not hear God in these events. Instead, Elijah heard the Lord in a small whisper. By this the prophet learned that sometimes God works in quiet ways.

There were in fact seven thousand who had not worshiped Baal. God sent Elijah to anoint three men who would ultimately destroy Ahab's house—Hazael of Aram, Jehu of Israel, and the prophet Elisha. The call of Elisha was the beginning of a large school of prophets (see 2 Kgs. 6:1-2).

Ahab's Victory (20:1-43). The Aramean king, Ben-Hadad, forged a coalition of thirty-two kings who besieged Samaria and held it hostage. Ahab, at the bidding of an unnamed prophet, secretly attacked the drunken Arameans, and the Lord granted Ahab's weaker armies a surprising victory. By this God demonstrated to Ahab that He was the true Lord of Israel. The next year the Arameans, believing that the Lord was a god only of the hills, attacked the city of Aphek located in a valley. God again granted victory to show that He ruled over hill and valley. In spite of God's grace, evil Ahab violated the rules of holy war and spared the life of Ben-Hadad. The Lord sent another prophet to the king to condemn Ahab for his neglect of the Lord's word. Ahab confirmed the truth of the message by announcing his own judgment.

Naboth's Vineyard (21:1-29). The evil plot against Naboth brought God's wrath against Ahab, including the deaths of Jezebel and his son Joram (1 Kgs. 22:37-38; 2 Kgs. 9:24-26,30-37). Because of the law of Moses, Naboth refused the king's request to acquire his vineyard. The law taught that God was the owner of Canaan and that the people, as its tenants, could not dispose of their land (Lev. 25:23; Num. 27:1-11; 36:1-12). Ahab, perhaps respecting the law of God more highly than Jezebel, only sulked about the refusal whereas Jezebel took steps to steal the land. She sent letters to powerful leaders of Jezreel to entrap Naboth with false charges of sedition and blasphemy. He was executed for these crimes, and his land was gobbled up by Jezebel and Ahab.

Yet their murder of Naboth did not go unnoticed. Elijah delivered God's denunciation in the very vineyard Jezebel conspired to get. Although Ahab was the passive player in this evil deed, he was held responsible for failing to stop his wicked wife. The prophet predicted that in the place the dogs licked the blood of Naboth, Ahab's blood also would be the delight of the city's stray dogs. Jezebel also would be a delicacy for the ravenous hounds of Jezreel.

Ahab repented when he heard the word of the Lord. Though he was the most wicked man of Israel, God took mercy on him and prolonged his life. This postponement did not mean, however, that God had changed His opinion on the character of Ahab's reign (see 22:37-38).

Micaiah's Prophecy and Ahab's Death (22:1-53). A monument of the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III tells how he fought the united armies of Ahab and Ben-Hadad at Qarqar on the Orontes River in 853 b.c. (see 20:34). The result was probably a stalemate. When the Assyrians retreated, Ben-Hadad renewed his hostilities by capturing Ramoth Gilead near the border of Israel (see 2 Kgs. 10:32-33). Jehoshaphat, the king of Judah, joined Ahab to fight the Arameans. Jehoshaphat was not satisfied with the prophets at Ahab's court and insisted on hearing from the prophet of the Lord. Micaiah, brought from Ahab's prison, predicted that Ahab would be killed in defeat. Ahab ridiculed his prophecy. But Micaiah told him how in a vision he had seen God send a deceiving spirit to mislead Ahab's counselors.

This vision does not mean that Micaiah believed God was a liar. This vision was a pictorial way to explain that God had permitted the false prophets to mislead Ahab to effect His divine judgment.

Ahab went into the battle disguised, but God found him through a bowman's arrow! Ahab's bloody chariot was washed in Samaria, and his blood was licked by dogs, just as the word of the Lord had said (see 21:19).

Jehoshaphat's twenty-five-year reign continued the religious reforms of his father Asa. Meanwhile, Ahaziah followed his father Ahab by worshiping Baal. His two-year reign was shortened by the judgment of God (see 2 Kgs. 1:1-18).

Theological and Ethical Significance. First Kings, like Deuteronomy, warns against forgetting God in times of economic prosperity. Having known material abundance, many today have left God out of their lives as the ancient Israelites did. Having abandoned faith, many have compromised their values to those of pagan society. The collapse of Israelite society warns of the consequences of sin.

First Kings reveals the power of the word of God in shaping history. The courage of those, like Elijah, whose hearts were captive to the word of God challenges today's Christians to let their presence be felt. After the prophet Micaiah had seen Yahweh's throne room, he was not impressed by King Ahab's threats. Those of us who have experienced the height and depth and breadth of God's love in Christ Jesus should be bold to speak God's word of judgment and grace to our world.

The history of Israel and Judah is the story of a people's failure to fulfill God's purpose for them. God, however, is faithful in spite of human failure. Though we are called to obedience, our hope lies in God's grace. We see this grace most clearly in Jesus Christ, "who as to his human nature was a descendant of David" (Rom. 1:3).

House, Paul R. 1, 2 Kings. New American Commentary. Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1995.

McNeeley, Richard I. First and Second Kings. Chicago: Moody, 1978.

Millard, Alan. 1 Kings–2 Chronicles. Ft. Washington, PA: Christian Literature Crusade. London: Scripture Union, 1985.

Vos, Howard F. 1, 2 Kings. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1989.