2 Samuel

Share

This resource is exclusive for PLUS Members

Upgrade now and receive:

- Ad-Free Experience: Enjoy uninterrupted access.

- Exclusive Commentaries: Dive deeper with in-depth insights.

- Advanced Study Tools: Powerful search and comparison features.

- Premium Guides & Articles: Unlock for a more comprehensive study.

When Bathsheba learned of her pregnancy, David attempted to cover up his sin. He sent for her husband, Uriah the Hittite, who was in the field of battle. Uriah refused to go home to his wife, even at David's insistence. Uriah did not want to enjoy his wife and home when the ark and armies of God were on the battlefield.

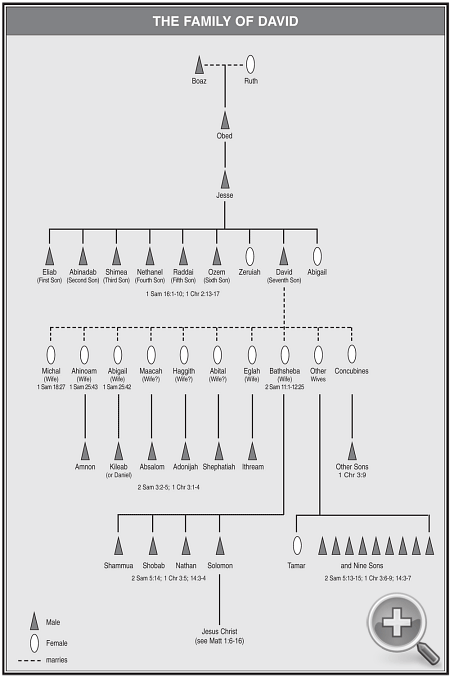

CHART: The Family of David

In desperation David plotted with the aid of Joab to murder Uriah by exposing him to the Ammonites in battle. The plot succeeded, and David took Bathsheba as his wife. The sin, however, did not go unnoticed, for "the thing David had done displeased the Lord."

Nathan's Oracle (12:1-31). About one year later, God sent Nathan to confront David. Nathan told a parable of a poor man's only ewe lamb taken away by a rich man for his selfish pleasure. David, who as king was responsible for justice in the land, burned with anger against the culprit. Unwittingly, David condemned himself. Nathan accused the king, "You are the man! Nathan declared God's judgment. Because he murdered Uriah by the sword, his household would likewise experience the sword. Since he took the wife of another man, David's wives would be taken. And though David sinned in secret, he would be publicly humiliated before all Israel (see 15:16; 16:21-22). These curses were fulfilled by the deaths of three of David's sons (Amnon, Absalom, and Adonijah) and the strife David's reign experienced toward the end of his life.

To David's credit, however, he did not shirk his guilt as Saul did when Samuel accused him (see 1 Sam. 15). David confessed his guilt openly and lamented his spiritual impurity (see Ps. 51). The judgment of God began with the child of David and Bathsheba. David prayed and fasted earnestly for the child's life. David had felt the heavy hand of God's judgment, but he also knew God's mercies. For that reason he prayed, believing God might deliver the child. Though the child was not spared, David believed that he would see the child again. In the midst of His chastening, God also was merciful to David and Bathsheba. God gave them another child, Solomon, whom the Lord named Jedidiah ("beloved of the Lord"). From their union came the king who would build the Lord's temple and rule Israel during its golden age. Evidence of God's continued forgiveness was Israel's victory over the Ammonites—this time led by David himself.

Absalom Murders Amnon (13:1-39). Although God forgave David, the consequences of his sin were immediately seen in his household. Just as David had lusted for Bathsheba, Amnon, the king's eldest son, desired his half-sister Tamar. He lured Tamar into his private quarters and raped her. However, his guilt was too great for his conscience, and he despised her afterward. He dismissed her, and she took refuge in the house of Absalom, her brother.

David, like Eli and Samuel, had no control over his sons. Absalom harbored his hatred for Amnon for two years until an occasion arose to kill him. Absalom held a festival attended by Amnon. At the command, Absalom's servants murdered Amnon. Absalom fled to Geshur where he took refuge with his maternal grandfather, Talmi, the king of Geshur. David wept for his son Amnon, who was special to the king as his eldest and successor to the throne. Yet he longed to see Absalom for the three years they were estranged.

Absalom Returns (14:1-33). Perhaps out of concern for the state of the kingdom, Joab wanted David's potential successor returned to the royal house. Similar to Nathan's ruse (chap. 12), Joab sent to the king a woman of Tekoa who pretended to be a woman in mourning. She sought the king's mercy on her only surviving son, who had murdered his brother. When David ruled that the son should be spared, the woman challenged David to reconsider his banishment of his own son Absalom. David agreed and dispatched Joab to retrieve him. David, however, refused to see Absalom's face upon his return to Jerusalem.

Absalom's Coup (15:1-37). Four years later the crown prince mounted an insurrection against the king by taking the king's place in the eyes of the people. Ironically, David's kingdom almost collapsed as a result of his own mishandling of his subjects rather than external threats. Absalom began to play the role of king. He had a private standing guard and functioned as final arbiter of judicial cases. Absalom stole away the hearts of the people, and he attempted to steal the kingdom from David. At Hebron, where his father had been declared king, Absalom's coconspirators acclaimed him king. Among their ranks was David's political advisor, Ahithophel.

Joined by a small but loyal contingency of Kerethites and Pelethites, David fled across the Kidron Valley toward the desert. He left behind his royal harem. Ittai the Gittite and his six hundred mercenary soldiers (Philistines from Gath) went with David. David sent Zadok and Abiathar back to Jerusalem with the ark of the Lord. David knew that the ark belonged in the house of God. He believed that if God so desired he would return one day to see the holy place of the Lord. The two priests, as prophetic seers, could aid David by learning of Absalom's plans and inquiring of the Lord in his behalf. Also, David countered the wisdom of Ahithophel by ordering Hushai the Arkite to remain in Absalom's service in order to confound the coup's strategy.

David's Anguish in Flight (16:1-23). The dark shadow of Saul again was cast over David as he fled his kingdom. Ziba, Saul's servant and manager of Mephibosheth's estate, maliciously defamed Mephibosheth to better himself (see 19:24-28). David granted the lands of Saul to Ziba. Shimei, a member of Saul's family, cursed David, calling him a "man of blood." This charge probably reflected the enmity many harbored against David. It may refer to David's turning members of Saul's family over to the Gibeonites for execution (chap. 21). Shimei attributed David's pain to the Lord's retribution. David perceived that Shimei's curse, though not altogether just, was part of God's chastening for his sin. David repelled Abishai's ambition to kill Saul's kinsman. David believed that God's vengeance or mercies alone would decide his and Shimei's fates.

Meanwhile, Hushai arrived in Jerusalem to win Absalom's favor. Absalom, not yet ready to trust Hushai, turned to Ahithophel for advice. He counseled Absalom to announce his takeover by the symbolic gesture of publicly sleeping with David's concubines (see 1 Kgs. 2:17-25). Absalom's incestuous act thus fulfilled Nathan's prophecy. The narrator compared the political adeptness of Ahithophel to the word of God revealed to the prophets.

Ahithophel's Advice (17:1-29). Hushai's task was a formidable one. Ahithophel advised Absalom to attack David while his troops were in disarray. This time Absalom heard the second opinion of Hushai, who argued that such a tactic would fail because of David's wily experience in warfare. Absalom postponed his attack, which meant that David had the opportunity to withdraw. The Lord "determined to frustrate the good advice of Ahithophel" and thereby doomed Absalom (see 15:34). The outcome of the war was decided before the first blow was struck.

Absalom's strategy was relayed to David's camp at the river fords through Jonathan and Ahimaaz, the sons of Zadok and Abiathar (see 15:35-36). Meanwhile, the wicked Ahithophel took his own life because he knew that Hushai's plan meant the end of Absalom's kingdom (15:15-23).

David in exile set up his provisional base in Mahanaim across the Jordan (see 2:8). Absalom established his military command by giving Amasa, Joab's relative, charge of the army. While Absalom organized for battle, David's friends—Shobi, Makir, and Barzilli—refreshed his fatigued army.

Absalom's Death (18:1-33). The story of Absalom's death focuses on David as father rather than as king. David remained behind the battle lines at the advice of his troops. He dispatched his commanders, instructing them to care for Absalom's life. Absalom, on the other hand, entered into the battle as it raged in the forests of Ephraim and beyond. The terrain was so precarious that more died from its pits and thickets than the sword. Absalom himself was its victim. He was caught by the head (see 14:26) in a tree and was suspended in midair. Though reminded of David's instructions to spare Absalom, Joab killed the helpless prince. The tragedy and disgrace of how Absalom died was even sadder because he had no heir. His three sons had apparently also died (see 14:27).

The story's detailed description of the two messengers and David's hopes dashed by their news accentuates the anguish of David the father. David's sin had spelled disaster for his family and crippled his own soul: "O my son Absalom! My son, my son Absalom. If only I had died instead of you—O Absalom, my son!"

David Returns (19:1-43). Joab continued to place the state of the nation above the feelings of the king. The aftermath of the war required a stronger show of Davidic leadership. Joab rebuked David for mourning the death of his enemies instead of greeting his triumphant soldiers. David took his place at the gate to receive his troops.

The tribes of Israel urged their leaders to reinstall David as their king. The men of Judah were initially reluctant. David replaced Joab with Amasa in a gesture of reconciliation. No doubt, Joab's demotion was also due to his killing of Absalom. The king also extended his generosity by sparing Shimei's life, hearing out the explanation of Mephibosheth, and sharing Saul's inheritance with Ziba in spite of his treachery. Furthermore, he welcomed to his court the son of his loyal advisor Barzillai.

The undercurrent of strife between Israel and Judah became apparent when the men of Israel were left out of the welcoming party that ushered David home. They interpreted this as exclusion from David's kingdom. The succession of northern tribes from Jerusalem occurred in the reign of David's grandson, Rehoboam (see 1 Kgs. 12:16-20).

Sheba's Revolt (20:1-26). The conclusion of this section concerning David's troubles appropriately ends with yet another rebellion. Sheba, a Benjamite, led an insurrection against David. The tribe of Benjamin, the kin of King Saul, had a longstanding feud with David as evidenced already by Shimei (16:7). Now fueled by animosity against Judah, Sheba seized the opportunity to rally the men of Israel to support his coup.

Amasa's slowness to attend to the rebellion forced David to appoint Abishai and Joab to deal with Sheba. When Amasa finally joined Joab's campaign, Joab greeted him with a treacherous kiss and then thrust his sword into Amasa's belly. Meanwhile, Sheba took refuge in Abel Beth Maacah, where the Judahites besieged the city. The people of Israel must have been skeptical of Sheba's chances for success. A woman of the city convinced its citizens to offer the head of Sheba to Joab, thereby averting the city's massacre and ending the schism.

The author concluded this section with a brief report on David's bureaucracy. This final listing of David's officials is similar to 8:15-18 with two important differences. There is no mention of slave labor in David's earlier administration, and also David's sons are absent.

The last section of the book is an appendix to David's career as the Lord's anointed. Here the emphasis falls on David's praise for God's sovereign mercies and the mighty warriors the Lord used in the service of the king. The stories of famine, war, and pestilence resulting from Israel's sin were fitting reminders that no king was above the word of the Lord.

God Avenges (21:1-22). A three-year famine caused David to inquire how Israel had offended the Lord. It was common in the Old Testament to attribute such catastrophies to the Lord's intervention. King Saul had breached Israel's longstanding covenant with the Gibeonites (see Josh. 9:25-27). Although 1 Samuel does not narrate Saul's murder of these Amorites (who resided in his homeland of Benjamin), such an act was consistent with Saul's policies (see 1 Sam. 22:16-19). David turned over seven descendants of Saul's house (sparing Mephibosheth) to the Gibeonites for execution to avenge their loss. David buried Saul's kin honorably with his and Jonathan's bones. The execution of Saul's kinsmen may have been the reason Shimei claimed David was guilty of bloodshed (see 16:7-8).

The catalog of wars against the Philistines is a commentary on the continued troubles in the reign of David but also a tribute to God's abiding favor as Israel prevailed over their foes.

Thanksgiving Hymn (22:1-51). The core of the appendix is David's tribute to the Lord. This song was also included in the Book of Psalms (Ps. 18). The occasion for David's thanksgiving was his deliverance from King Saul.

David recalled his cry for deliverance. He described the Lord's intervention in words reminiscent of His appearance at Mount Sinai (see Exod. 19; Ps. 68:7-18; Hab. 3). The Lord, awesome in might, came to his personal rescue because David was upright and faithful. God was his Lamp, Rock, and Shield of Salvation, giving David complete victory over all his enemies. The song concludes with a doxology.

Oracle (23:1-39). Although other words from David are recorded in the Old Testament books that follow (1 Kgs. 2:1-9; 1 Chr. 23:27), this oracle was David's last formal reflection on the enduring state of his royal house under the covenant care of the Lord. The term "oracle" commonly introduces prophetic address (Num. 23:7; Isa. 14:28; Mal. 1:1). David declared by the Spirit that God had chosen him from all Israel and made an everlasting covenant with his lineage. Those who opposed him would be cast aside as thorns for the fire. This messianic description is fully realized in Jesus Christ, who as David's son establishes the rule of God in the earth.

The catalog of mighty men and their exploits was another tribute to God's enablement of David. Among David's armies were two elite groups of champions who served as the king's bodyguard and special fighting force (see 21:15-22; 1 Chr. 11:10-47). The first group consisted of the "Three" whose exploits against the Philistines were renown (see the cave of Adullam, 1 Sam. 22). Abishai and Benaiah were singled out, although they were not as great as the "Three," because they held high honor in the annals of David's wars. The second group, the "Thirty," is also listed, giving a total count of thirty-seven heroes (including Joab, 23:24-39).

David's Pride (24:1-25). The final episode of the appendix concerns the plague the Lord brought against Israel because of David's sin. It parallels the beginning story of the appendix where Israel suffered famine because of Saul's sin (21:1-14). The specific reason for God's anger at Israel is unstated. The Lord, however, used David's census to chasten the people by plague. In the parallel passage (1 Chr. 21:1) the author explained that the immediate cause for David's sin was the work of Satan.

David's taking of the census was an indication of his pride and self-reliance. In the law the taking of a census required an atonement price to avert plague (Exod. 30:11-16). God instructed the prophet Gad to announce His judgment on Israel. God presented David a choice of three punishments—famine, plague, or war. These three sanctions were the curses God threatened to bring upon Israel for breaking the covenant (Deut. 28). David wisely placed himself at the mercy of God and not the temperament of man. The Lord punished Israel by a devastating plague. David confessed that he was guilty for misleading the sheep of Israel.

To make atonement for Israel, the prophet Gad instructed David to build an altar at the threshing floor of Araunah. There David had seen the avenging angel carry out the deadly plague. He would later choose this site for the building of the temple (1 Chr. 22:1).

Araunah offered to give the floor to the king, but David knew that acceptable atonement required a price. He built the altar, offered sacrifices, and prayed in behalf of his people. The Lord acknowledged David's intercession, and the plague ceased.

Ethical and Theological Significance. David's story, like Romans 7:7-25, speaks to the Christian's experience of sin. David was a man after God's own heart (1 Sam. 13:14). Like Paul, he could have said, "In my inner being I delight in God's law" (Rom. 7:22). But like Paul, David saw "another law at work in the members of [his] body, ... making [him] a prisoner of the law of sin" (7:23). David coveted Uriah's wife, and "sin sprang to life" (7:9). With Uriah's murder, David's sin became "utterly sinful" (7:13).

Nathan's parable roused David's moral outrage at his sin (2 Sam. 12). Today Scripture functions like Nathan's tale to help us see what we are really like. David saw and experienced heartbreak over his sin.

David suffered short-and long-term consequences of his sin. His sin did not, however, thwart God's ultimate, saving purpose for and through him. "In all things God works for the good of those who love him" (Rom. 8:28). God worked through the lives of David and Bathsheba to give Israel its next king (Solomon) and, in time, its Messiah (Matt. 1:6). God continues to work through the lives of repentant sinners. "Thanks be to God—through Jesus Christ our Lord!" (Rom. 7:25).

Baldwin, Joyce G. 1 & 2 Samuel. Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1988.

Laney, J. Carl. First and Second Samuel. Chicago: Moody, 1982.