Genesis

Share

This resource is exclusive for PLUS Members

Upgrade now and receive:

- Ad-Free Experience: Enjoy uninterrupted access.

- Exclusive Commentaries: Dive deeper with in-depth insights.

- Advanced Study Tools: Powerful search and comparison features.

- Premium Guides & Articles: Unlock for a more comprehensive study.

Blessing Neighbors (18:16-19:22). God reminded Abraham that he was the chosen means of blessing the nations. As an illustration of what that meant, Yahweh revealed to Abraham that He was going to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah, cities whose sinfulness was beyond remedy. Abraham was aware that this implied the death of his own nephew Lot, who lived in Sodom. Abraham exercised his ministry of mediation by pleading with the Lord to spare the righteous and thus the cities in which they lived. Though not even ten righteous ones could be found and the cities therefore were overwhelmed in judgment, Abraham's role as the one in whom the nations could find blessing is clearly seen.

Promise Threatened (20:1-18). Abraham's encounter with Abimelech of Gerar also testifies to Abraham's role as mediator. He had lied to Abimelech concerning Sarah, maintaining that she was only his sister. Abimelech took Sarah into his own harem, putting God's promise of offspring through Sarah in jeopardy. Before matters could proceed further, the Lord revealed to Abimelech that Abra ham was a prophet, one whose prayers were effective. Then the plague that Yahweh had brought upon Abimelech because of his dealings with Sarah was removed in response to Abraham's intercession. Once more Abraham's function as dispenser of blessing and cursing is evident.

Promise Fulfilled (21:1-21). At last Isaac, the covenant son, was born. Through Ishmael, God honored His promise that not only the Hebrews but "many nations" would call Abraham "Father" (see 25:12-18).

Obedience and Blessing (22:1-19). Within a few years the Lord tested Abraham by commanding him to offer his covenant son as a burnt offering. The intent was to teach Abraham that covenant blessing requires total covenant commitment and obedience. The narrative also stresses that covenant obedience brings fresh bestowal of covenant blessing. Abraham's willingness to surrender his son guaranteed all the more the fulfillment of God's promises to him.

Isaac fulfilled a passive linking role quite unlike the other patriarchs, who took an active role in the outworkings of God's promises. Already Abraham had waited for Isaac's birth; Abraham stood ready to offer Isaac as a sacrifice. Following the death and burial of Sarah, Abraham made arrangements for Isaac to take a wife from among his own kinfolk of Aramea. Abraham thus worked to ensure that the promise of offspring would continue into the next generation. This done, Abraham died (25:7-8) and was buried with his wife by his sons Ishmael and Isaac. Isaac rarely occupied the center stage. In the following years Isaac, who had been the object of his father's actions, became an object in his son Jacob's struggle for the promises (27:1-40).

A rare scene focusing on Isaac pictures him as the link through whom God's promises to receive land and to be a source of blessing for the nations were fulfilled. The Lord sent Isaac to live among the Philistines of Gerar as Abraham had done. There Isaac unwillingly blessed the nations by digging wells which the Philistines appropriated to their own use. Isaac and his clan proved to be such a source of nourishment to their neighbors that Abimelech their king made a covenant with Isaac, recognizing his claim in the promised land.

Isaac served as a passive link with God's promises to Abraham. In contrast, Isaac's younger son, Jacob, fought throughout his life for the very best that God had promised to give.

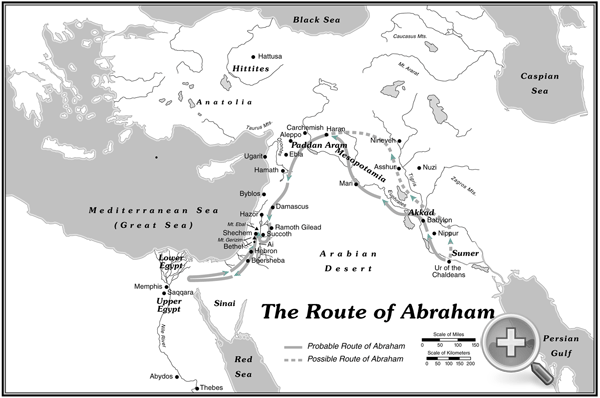

MAP: The Route of Abraham

Beginning of Struggle (25:19-26). Just as the barrenness of Sarah called for Abraham to trust God for offspring, that same deficiency in Rebekah called for earnest prayer from her husband Isaac. Faithful to His promise to Abraham, Yahweh responded and gave not one but two sons, Esau and Jacob. Jacob's grasping Esau's heel in an effort to be the firstborn introduces the major theme of the Jacob stories—Jacob's struggle for the promised blessings.

Struggle for Birthright (25:27-34). Contrary to the norms of succession and inheritance, the Lord gave to Jacob the rights of the firstborn, though on the human level Jacob manipulated his brother in order to receive them. Esau, as the older son of Isaac, should have inherited the birthright, the claim to family leadership. He forfeited that, however, in a moment of self-indulgence.

Struggle for Blessing (26:34-28:9). Esau still retained his position as heir of the covenant promises in succession to Abraham and Isaac. But when it was apparent through his marriages to Hittite women that he was unworthy of covenant privilege, his mother, Rebekah, set about to replace him with his brother Jacob.

When the day came for Isaac to designate Esau as the recipient of God's promised blessing, Jacob appeared in his place. Blind Isaac, deceived by the substitution, granted his irrevocable blessing. In the ancient world the speaking of a blessing, like the signing of a contract in our day, gave the words binding force. Jacob thus controlled both the birthright and the blessing. Though the means of their acquisition was anything but honorable, the Lord had foretold Jacob's triumph on the occasion of the birth of the twins (25:23).

Enraged by this turn of events, Esau plotted to kill his brother. Rebekah urged Jacob to flee for his life to Paddan-Aram, her homeland, so that he might also acquire a wife from among their kin.

God's Faithfulness (28:10-22). God's watchcare became apparent at Bethel, where Jacob encountered Yahweh in a dream. He revealed Himself to Jacob as the God of his fathers, the one who would continue the covenant promises through him.

Struggle Continues (29:1-31:55). Thus encouraged, Jacob went on to Haran, where he struggled with his uncle Laban for the right to marry his daughters Leah and Rachel. God's promise of many offspring began to be realized as Jacob fathered eleven sons and a daughter in his wives' struggle for children. In his struggle against scheming Uncle Laban, Jacob became prosperous beyond his wildest expectations. By stealing the household gods, Rachel joined Jacob in the struggle against Laban. With Laban intent on revenge, only God's intervention in a dream brought a peaceful end to the struggle with Jacob.

Promised Land (32:1-33:17). Finally, after twenty years Jacob returned to his homeland. On the way he learned that Esau was coming to meet him. Fearing that his own efforts to safeguard himself from Esau's revenge were inadequate, Jacob entreated the Lord to deliver him. The Lord again appeared to Jacob, this time as a human foe, and wrestled with the patriarch through the night. Impressed with his persistent struggle, the "man" blessed Jacob with a change of name ( Jacob to Israel, prince of God). The deceiver ( ya akob) had become a nobleman, one fit to rule through the authority of the sovereign God. The subsequent encounter with Esau proved to be peaceful. Indeed, Jacob saw in Esau's forgiveness a reflection of God's face.

Threat of Assimilation (33:18-34:31). Jacob moved on into Canaan, coming first to Shechem, the first stopping place of his grandfather Abraham (see 12:6). Having secured property there, Jacob built an altar.

The rape of Dinah graphically illustrates the loose morals of the native Canaanites. Shechem's proposal of marriage illustrates the threat of intermarriage. The slaughter of the men of Shechem anticipates Israel's conquest of the land under Joshua.

Reaffirming the Promises (35:1-36:43). Jacob traveled on to Bethel, again in the footsteps of Abraham (see 12:8). There, as he had before, Jacob saw the Lord in a vision and received yet another promise of the divine presence and blessing. He would father nations and kings and would inherit the land of his fathers. The list of his immediate descendants attests to the onset of promise fulfillment. Even Esau, who had to settle for a secondary blessing (27:39-40), gave rise to a mighty people.

Israel's role as the people of promise was being jeopardized by their acceptance of the loose moral standards of the native Canaanites. The incest between Reuben and his father's ser-vant-wife (35:22) hints at that moral compromise. Judah's marriage to the Canaanite Shua and his later affair with his own daughter-in-law, Tamar, makes the danger clear. To preserve His people, Yahweh removed them from that sinful environment to Egypt, where they could mature into the covenant nation that He was preparing them to be.

This explains the Joseph story. His brothers sold him to Egypt to be rid of their brother the dreamer. God, however, used their act of hate as an opportunity to save Israel from both physical famine and spiritual extinction. The rise of Joseph to a position of authority in Egypt in fulfillment of his God-given dreams illustrates the Lord's blessing upon His people. Joseph's wisdom in administering the agricultural affairs of Egypt again fulfilled God's promise that "I will bless him who blesses you." What appeared to be a series of blunders and injustices in Joseph's early experiences proved to be God at work in unseen ways to demonstrate His sovereign, kingdom work among the nations.

No one was more aware of this than Joseph, at least in later years. After he had revealed himself to his brothers, he said, "God sent me ahead of you to preserve for you a remnant on earth and to save your lives by a great deliverance." Years later after Jacob's death, when Joseph's brothers feared his revenge, he reminded them that they had intended to harm him, "but God intended it for good to accomplish ... the saving of many lives." Human tragedy had become the occasion of divine triumph. Joseph's dying wish—to be buried in the land of promise—looks past the future tragedy of Israel's experience of slavery and anticipates God's triumph in the exodus.

Contemporary Significance. One obvious contribution of the Book of Genesis to the modern world is its explanation of the origins of things that could be understood in no other way. That is, it has scientific and historical value even if that is not its primary purpose.

More fundamentally, Genesis deals with the essence of what it means to be human beings created as the image of God. Who are we? Why are we? What are we to do? Failure to appreciate God's purpose for humanity has resulted in chaotic, purposeless thought and action. Ultimately, life without true knowledge of human nature as the image of God and human function as stewards of God's creation is life without a sense of meaning. When one lives out life in light of Genesis, life is seen as being in touch and in tune with the God of the universe. God's rule becomes a reality as human beings conform to His goals for His creation. Genesis outlines the Creator's intentions.

As sinners we are unable to realize God's purpose for our lives through our own efforts. Only God's intervention brings promise to our lives. Our salvation is God's work.

Ethical Value. The awful effect of sin is one of the striking themes of Genesis. Sin frustrated the purposes of God for the human race. Sin had to be addressed before those purposes could be realized. Genesis teaches the heinousness and seriousness of sin and its tragic repercussions.

In addition to the story of "the fall," narrative after narrative in Genesis shows people how to live victoriously in the face of anti-God elements at work in this fallen world and describes what happens when they fail to do so. Cain, through lack of faith, dishonored God and then killed his brother. Lamech, in boasting pride, revealed the absurdities of humanistic views of life. The intermingling of angelic and human societies shows the inevitable result of breaking the bonds of God-ordained positions in life. The pride of the Babel tower builders demonstrates the arrogance of people who seek to make a name for themselves rather than to honor the name of the Lord.

The models of faith and obedi-ence—Abel, Enoch, Noah, Abraham, and Joseph—are instructive as well. Their commitment to righteousness and the integrity of lifestyle speak eloquently of what it means to be a kingdom citizen, faithfully at work discharging the high and holy elements of that call.

Butler, Trent C. "Genesis." Holman Bible Dictionary. Nashville: Holman, 1991.

Coats, George W. Genesis, with an Introduction to Narrative Literature. Forms of Old Testament Literature, vol. 1. Ed. R. Knierim and G. Tucker. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1983.

Garrett, Duane. Rethinking Genesis. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1991.

Kidner, Derek. Genesis: An Introduction and Commentary. London: Tyndale, 1967.

Kikawada, I. M., and Arthur Quinn, Before Abraham Was. Nashville: Abingdon, 1985.

Leupold, H. C. Exposition of Genesis. 2 vols. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1942.

Mathews, Kenneth A. Genesis 1-11:26. The New American Commentary. Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1996.

Ross, Allen P. Creation and Blessing. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1988.