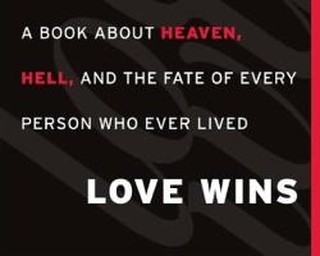

A Review of Rob Bell’s 'Love Wins'

Share

This is a chapter-by-chapter review of Rob Bell's most recent book, Love Wins. I write as a professor, as a pastor and as a parent. Thus, it is my desire to be objective, edifying and to write the truth in love.

Preface: Millions of Us

Bell correctly identifies love as one of God's main attributes, "Jesus' story is first and foremost about the love of God for every single one of us…'For God so loved the world…' That's why Jesus came. That's his message. That's where the life is found" (p. vii). It is true that God is loving, gracious and merciful; He is also holy, righteous and just. The author is reacting against people who, he says, have "hijacked" Jesus' story.

"There are a growing number of us who have become acutely aware that Jesus' story has been hijacked by a number of other stories, stories Jesus isn't interested in telling, because they have nothing to do with what He came to do. The plot has been lost, and it's time to reclaim it" (p. vii-viii). The topics of heaven and hell quickly come to the forefront; these topics are not new, and Bell admits Jesus speaks of both. However, he is taking to task those who believe in separate eternal states/destinations. "A staggering number of people have been taught that a select few Christians will spend forever in a peaceful, joyous place called heaven, while the rest of humanity spends forever in torment and punishment in hell with no chance for anything better" (p. viii).

Bell uses strong words to contradict those who believe in a heaven for those who accept Christ and a hell for those who reject Him. "It's been clearly communicated to many that this belief is a central truth of the Christian faith and to reject it is, in essence, to reject Jesus. This is misguided and toxic and ultimately subverts the contagious spread of Jesus' message of love, peace, forgiveness and joy that our world desperately needs to hear" (p. viii). The author emphasizes that what he is saying has been said before, and he suggests that this was accepted as orthodox teaching.

Chapter 1: What About the Flat Tire?

Rob Bell loves questions; however, he does not always draw a clear distinction between rhetorical questions and those that demand an answer. He asks, "Has God created millions of people over tens of thousands of years who are going to spend eternity in anguish?" (p. 2). Is Rob Bell saying here that millions of people will not spend eternity in anguish? He continues, "What happens when a 15-year-old atheist dies?" (p. 4). Is Rob Bell saying that because of his age, the atheist should get a pass? He also asks, "What about people who have never said the prayer and don't claim to be Christians, but live a more Christlike life than some Christians?" (p. 6). Is Rob Bell implying that a non-Christian can live a Christlike life? Does the Bible teach that a non-believer can live a Christlike life apart from Christ? The concept comes across as oxymoronic.

The book is confusing in that, after asking these questions, Rob Bell correctly affirms, "All that matters is how you respond to Jesus" (p. 7). This truth is followed by the question, "Which Jesus?" Evangelical Christians would hope the answer is Jesus of Nazareth, the Messiah who was revealed to us in the Bible. Instead of clear, biblical answers, more questions arise. Is he implying there is more than one Jesus? Asking questions such as these, it could be interpreted that Bell is referring to a crossless, miracleless Jesus that many have substituted for actual, historical Jesus of the Bible.

Bell correctly says, "the phrase 'personal relationship' is found nowhere in the Bible" (p. 10), but he does not discuss the relational nature of God's covenants with His people. The covenant formula, "I will be your [or their] God, and you [or they] will be My people" (Leviticus 26:12; Jeremiah 7:23, Jeremiah 24:7, Jeremiah 30:22, Jeremiah 31:33, Jeremiah 32:38; Ezekiel 11:20, Ezekiel 36:28, Ezekiel 37:23, Ezekiel 37:27; Zechariah 8:8; 2 Corinthians 6:16) appears frequently. The language of relationship pervades Scripture. God reveals Himself as God the Father; Jesus teaches His disciples to pray, "Our Father..." (Matthew 6:9); through Christ, we are adopted in the family of God (Galatians 4:4-5); Jesus calls us "brothers" (Hebrews 2:12).

Then, Bell presents a barrage of questions asking, "What saves you? Is it what you say, or who you are, or what you do, or what you say you're going to do, or who your friends are, or who you're married to, or whether you give birth to children? Or is it what questions you're asked? Or is it what questions you ask in return? Or is it whether you do what you're told and go into the city?" (pp. 16-17). Although Bell does not answer these questions, he promises at the end of the chapter, "But this isn't just a book of questions. It's a book of responses to these questions" (p. 19).

Chapter 2: Here Is the New There

In this chapter, Bell argues that heaven should not be understood as something we simply are looking forward to, but as something we can start experiencing here on earth. To support this idea, he uses the story from Matthew 19 where a rich man asks Jesus: "Teacher, what good thing must I do to get eternal life?" Part of Jesus' response is, "There is only One who is good. If you want to enter life, keep the commandments." Then, Bell asks, "'Enter life?'…This isn't what Jesus was supposed to say…Jesus then tells him, 'Go, sell your possessions, and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven.'…Shouldn't Jesus have given a clear answer to the man's obvious desire to know how to go to heaven when he dies?" (pp. 26-28). Bell inquires, "Is that why he walks away—because Jesus blew a perfectly good 'evangelistic' opportunity?…The answer, it turns out, is in the question. When the man asks about getting 'eternal life,' he isn't asking about how to go to heaven when he dies. This wasn't a concern for the man or Jesus. This is why Jesus didn't tell people how to 'go to heaven.' It wasn't what Jesus came to do" (pp. 29-30). In contradiction to Bell's claim, Jesus said in John 14:1-6 that He goes to prepare a place for His followers.

Bell's treatment of prophecy is commendable; he recognizes that while the prophets preach against sin and warn of God's coming judgment, they also preach of restoration. "And so in the midst of prophets' announcements about God's judgment we also find promises about mercy and grace" (p. 39). Unfortunately, his next statement fails to see the eschatological focus of the prophets. "They did not talk about a future life somewhere else, because they anticipated a coming day when the world would be restored, renewed and redeemed and there would be peace on earth" (p. 40). Isaiah wrote of a new heaven and a new earth: "For behold, I create new heavens and a new earth, and the former things shall not be remembered or come into mind" (Isaiah 65:17). Through Jeremiah, God spoke of the end times: "Behold, the days are coming, declares the Lord, when I will raise up for David a righteous Branch, and he shall reign as king and deal wisely, and shall execute justice and righteousness in the land. In his days Judah will be saved, and Israel will dwell securely. And this is the name by which he will be called: 'The Lord is our righteousness'" (Jeremiah 23:5-6).

Bell also confuses the genre of a passage of scripture. Bell said, "In the Genesis poem that begins the Bible, life is a pulsing, progressing, evolving, dynamic reality in which tomorrow will not be a repeat of today, because things are…going somewhere" (p. 44). Genesis 1 is not poetry, but prose. His choice of the word evolving may also be interpreted as suspect, and some may feel Bell is leaving room for the possibility of evolution.

Bell also asks, "Think about the single mom, trying to raise kids…Is she the last who Jesus says will be first? Does God say to her, 'You're the kind of person I can run the world with'?" (p. 53). Does Rob Bell intend to imply this woman can be first in God's kingdom because she was faithful in raising her children, apart from a true relationship with God? If so, he is contradicting Scripture; Luke wrote in Acts 4:12, "There is salvation in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given among men by which we must be saved."

Moving away from questions, he asserted, "Let me be clear: Heaven is not forever in the way we think of forever, as a uniform measurement of time, such as days and years, marching endlessly into the future. That's not a category or concept we find in the Bible" (p. 58). The Bible is clear that forever means "forever." "The Word of the Lord endures forever" (1 Peter 1:25); "Whoever does the will of God abides forever" (1 John 2:17); "And they will be tormented day and night forever and ever" (Revelation 20:10).

After a brief word study on the Greek term aion, Bell concludes that "when Jesus talked about heaven, He was talking about our present eternal, intense, real experiences of joy, peace and love in this life, this side of death and the age to come" (p. 58-59). An in-depth word study would reveal that Bell is mistaking the meaning of aion in saying that it does not mean "eternity;" a simple search reveals the word aion and its derivatives are used almost 200 times in the New Testament with the meaning of eternity, age/era or world/material universe.

Bell concludes the chapter with this challenge, which could be seen as arrogant, "So how do I answer questions about heaven? How would I summarize all that Jesus teaches? There's heaven now, somewhere else. There's heaven here, sometime else. Then there's Jesus' invitation to heaven here and now, in this moment, in this place. Try and paint that" (p. 62).

Chapter 3: Hell

Bell is partly correct when he affirms, "the Hebrew commentary on what happens after a person dies isn't very articulated or defined…For whatever reasons, the precise details of who goes where, when, how, with what and for how long simply aren't things the Hebrew writers were terribly concerned with" (p. 67). However, he omits two passages that clearly speak of eternal destinations. In Isaiah 65--Isaiah 66, the eighth century prophet talks of the new heaven and the new earth. Isaiah 66:24 is even quoted by Jesus saying, "They shall go out and look on the dead bodies of the men who have rebelled against Me. For their worm shall not die, their fire shall not be quenched, and they shall be an abhorrence to all flesh." The other passage that clearly speaks of two places of either eternal reward or punishment is in the Book of Daniel, "At that time shall arise Michael, the great prince who has charge of your people. There shall be a time of trouble, such as never has been since there was a nation till that time. At that time, your people shall be delivered, everyone whose name shall be found written in the book. Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt. Those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the sky above; and those who turn many to righteousness, like the stars forever and ever" (Daniel 12:1-3). The Daniel text points to the resurrection of the righteous and the wicked. These expressions occur only here in the Old Testament, and the word everlasting refers to time without end.

Bell's treatment of hell continues into the New Testament. He said, "The actual word hell is used roughly 12 times in the New Testament, almost exclusively by Jesus Himself" (p. 67). He correctly points out, "the Greek word that gets translated hell in English is the word Gehenna… the Valley of Hinnom…an actual valley on the south and west side of the city of Jerusalem" (p. 67). Unfortunately, he fails to see the relationship between the Valley of Hinnom and the orthodox view of hell, which is obvious in that he continues, "So the next time someone asks if you believe in an actual hell, you can say, 'Yes, I do believe my garbage goes somewhere…'" (p. 68). Jesus can be seen to speak of Gehenna in the context of destruction, unquenchable fire and as a contrast to entering life or the kingdom of God. In Matthew 10:28, "Do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. Rather fear Him who can destroy soul and body in hell." In Mark 9:43, "If your hand causes you to sin, cut it off. It is better for you to enter life crippled than with two hands to go to hell, to the unquenchable fire." Also, in Mark 9:47, "If your eye causes you to sin, tear it out. It is better for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye than with two eyes to be thrown into hell."

Bell correctly said, "The other Greek word is Hades…We find the word in Revelation 1, Revelation 6, Revelation 20, and in Acts 2…Jesus uses the word in Matthew 11 and Luke 10…and in the parable of the rich man and the beggar Lazarus in Luke 16" (p. 69). In his treatment of the story of the rich man and Lazarus, he incorrectly concludes, "What we see in Jesus' story about the rich man and Lazarus is an affirmation that there are all kinds of hells… in this life, and so we can only assume we can do the same in the next. There are individual hells and communal, society-wide hells; and Jesus teaches us to take both seriously. There is hell now, there is hell later; and Jesus teaches us to take both seriously" (p. 79). It should be noted that most biblical scholars would contradict Bell's claim that this story is a parable; parables traditionally have nameless characters and are introduced with a comparative.

One of the most extreme perspectives Bell presents is the insinuation that Sodom and Gomorrah's eternal destiny could be changed. "More bearable for Sodom and Gomorrah? He tells highly committed, pious, religious people that it will be better for Sodom and Gomorrah than them on judgment day? There is still hope?" (p. 84). Jesus in context compares two groups of people that will be eternally lost, not one that will be able to move from eternal damnation to eternal blessedness.

From a linguistic perspective, Bell's treatment of the Greek language is either dishonest or ignorant. In mentioning the sheep and the goats of Matthew 25, Bell affirms, "the goats are sent, in the Greek language, to an aion of kolazo… the phrase can mean 'a period of pruning,' 'a time of trimming' or an intense experience of correction." The truth is that the expression eis kolasin aionion used in Matthew 25:46 means "into eternal punishment" and is used in conjunction with "everlasting fire" and in contrast with "eternal life." No version of the Bible or evangelical commentary translates this expression the way Bell does. In this passage, Bell redefines hell; for him, hell is, "the very real consequences we experience when we reject the good and true and beautiful life that God has for us…the big, wide, terrible evil that comes from the secrets hidden deep within our hearts all the way to the massive, society-wide collapse and chaos that comes when we fail to live in God's world God's way" (p. 93). The problem with this view of hell is that it is not biblical; Jesus taught simply that there will be a bodily resurrection of the righteous and the wicked (John 5:28-29), with the righteous entering eternal life and the wicked, eternal punishment (Matthew 25:46).

Chapter 4: Does God Get What God Wants?

In this chapter, Bell seems to imply that if people choose to go to hell, God does not get what He wants, namely to take everyone to heaven. He asks, "Will all people be saved, or will God not get what God wants? Does this magnificent, mighty, marvelous God fail in the end?" (p. 98). He does not answer this question, which relies on fallible logic and a false dichotomy. One cannot rationally claim that God does not get what He wants, which is what Bell implies would happen if less than each person is saved. To say that God fails in this way because not everyone is saved is similar to saying God is not omnipotent because He cannot create square circles. A circle cannot be square; it goes against the nature of being a circle. In the same way, God cannot go against His own nature.

His next question is surreal, "What makes us think that after a lifetime, let alone hundreds or even thousands of years, somebody who has consciously chosen a particular path away from God suddenly wakes up one day and decides to head in the completely opposite direction?" (pp. 104-105). The Bible is clear on this issue; the author of Hebrews (whom Bell claims is a woman) writes, "Just as it is appointed for man to die once, and after that comes judgment, so Christ, having been offered once to bear the sins of many, will appear a second time, not to deal with sin, but to save those who are eagerly waiting for him" (Hebrews 9:27-28).

One can see how Bell might be labeled as an universalist when he makes such assertions, "given enough time, everybody will turn to God and find themselves in the joy and peace of God's presence. The love of God will melt every hard heart, and even the most 'depraved sinners' eventually will give up their resistance and turn to God…Could God say to someone truly humbled, broken and desperate for reconciliation, 'Sorry, too late?'" (pp. 107-108). Again, the variable, but non-negotiable entity of death gets in the way. Nowhere in the Bible does someone turn to God after he or she has died. Bell wants to support his claims by appealing to Genesis 18, "As Abraham asked: 'Will not the Judge of all the earth do right?'" (p. 109). The passage that follows shows how He did right; He judged Sodom and Gomorrah and destroyed them, "Then the Lord rained on Sodom and Gomorrah sulfur and fire from the Lord out of heaven. He overthrew those cities and all the valley and all the inhabitants of the cities, and what grew on the ground" (Genesis 19:24-25).

Rob Bell asks, "Will everybody be saved, or will some perish apart from God forever because of their choices? Those are questions, or more accurately, those are tensions we are free to leave fully intact. We don't need to resolve them or answer them because we can't; and so we simply respect them, creating space for the freedom that love requires" (p. 115). Bell is correct that there are some tensions in the Bible which we must leave unresolved, but the fact that people choose to reject God and thus "perish apart from God forever because of their choices" is not one of those tensions.

However, Bell correctly concludes the chapter by affirming one's freedom to choose. He says, "If we want hell, if we want heaven, they are ours. That's how love works. It can't be forced, manipulated or coerced. It always leave room for the other to decide. God says yes, we can have what we want, because love wins" (pp. 118-119).

Chapter 5: Dying to Live

In this chapter, Bell quite masterfully explains how Jesus became the ultimate sacrifice, accurately tying His death the to Old Testament sacrificial system. He describes the meaning of the cross saying, "What happened on the cross is like…a defendant going free, a relationship being reconciled, something lost being redeemed, a battle being won, a final sacrifice being offered, so that no one ever has to offer another one again" (p. 128). He continues by supporting the importance of the resurrection. "[The disciples'] encounters with Him led them to believe something massive had happened that had implications for the entire world" (p. 130).

He points to the significance of the number seven and ties this in with John's placing the raising of Lazarus from the dead as the seventh sign in his gospel. He ties this in with the seven days of creation concluding, "John is telling a huge story, one about God rescuing all of creation" (p. 134). Bell correctly points out that 1 John 2:2 does not speak of a limited atonement, "The pastor John writes to his people that Jesus is 'the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world' and that Jesus is 'the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not for only ours but also for the sins of the whole world'" (p. 135). This chapter is theologically rich, and while it provides more questions than answers, it does not generally carry any universalist implications.

Chapter 6: There Are Rocks Everywhere

The title of the chapter makes allusion to Paul's use of the Old Testament episode when God gave His people water to drink from the rock (Exodus 17:6-7). As Paul gave the church at Corinth a history lesson, he wrote that the people "drank from the spiritual Rock that followed them, and the Rock was Christ" (1 Corinthians 10:4). Bell then incorrectly concludes, "Paul finds Jesus there, in that rock, because Paul finds Jesus everywhere" (p. 144). Bell's exegetical skills are still found lacking. Paul identifies the manna in the wilderness as spiritual food, and the water from the rock as spiritual drink; Paul emphasizes the supernatural provision of the manna and the water in the wilderness. Because the rock is with the people at the beginning of their journey, as well as at the end (Exodus 17, Numbers 20), Paul says that Christ is the rock that was with them all along.

In his treatment of John 14:1-6, Bell mocks Jesus' claim of exclusivity. He writes, "John remembers Jesus saying, 'I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through Me.' What he doesn't say is how, when, or in what manner the mechanism functions that gets people to God through Him. He doesn't even say those coming to the Father through Him will know they are coming exclusively through Him" (p. 154). Somehow, Bell undermines Jesus' word and says that someone could make it to the Father without knowledge of Christ. Bell writes, "First, there is exclusivity. Jesus is the only way…Then there is inclusivity. The kind that is open to all religions, the kind that trusts that good people will get in [which he does not advocate]…Then there is an exclusivity on the other side of inclusivity. This kind insists Jesus is the way, but hold tightly to the assumption that the all-embracing, saving love of this particular Jesus the Christ will of course include all sorts of unexpected people from across the cultural spectrum" (pp. 154-155). Bell shockingly claims Jesus declares "He and He alone is saving everybody. Then He leaves the door open, creating all sorts of possibilities. He is as narrow as Himself and as wide as the universe" (p. 155).

Bell exhorts believers to suspend judgment, using John 3:17 as a proof text. He writes, "it is our responsibility to be extremely careful about making negative, decisive, lasting judgments about people's eternal destinies. As Jesus said, He 'did not come to judge the world, but to save the world' (p. 160). Bell should also have included Jesus' words: "Whoever believes in Him is not condemned, but whoever does not believe is condemned already, because he has not believed in the name of the only Son of God" (John 3:18). These words of Jesus may be negative and decisive, yet they remain true.

Chapter 7: The Good News Is Better than That

After retelling the story of "The Loving Father and His Two Lost Sons" (or "The Prodigal Son"), Bell concludes, "The difference between the two stories is, after all, the difference between heaven…and hell." Bell includes Tim Keller's The Prodigal God in his "Further Reading," yet his exegetical method does not follow Keller's. Keller's point is that the parable is about God's extravagant love for both lost sons, and Bell claims the parable is about heaven and hell. Keller also does a masterful job at pointing the relationship between the parable of the Loving Father, the parable of the Lost Sheep, and the parable of the Lost Coin. He even points out that by not finishing the parable of the Loving Father, Jesus was inviting His audience to respnd to the message. The Pharisees, who are represented by the older brother, were the ones who were supposed to go and search for the lost younger brother. Bell explains his view by claiming that for the older son, "hell is being at the party. That's what makes it so hellish. It's not an image of separation, but one of integration. In this story, heaven and hell are within each other, intertwined, interwoven, bumping up against each other" (p. 169-170). This intertwining of heaven and hell is neither biblically nor theologically sound. However, Bell is correct when he summarizes God's version of our story: "We are loved…in spite of our sins, failures, rebellion and hard hearts…God has made peace with us" (p. 172).

Bell borders on blasphemy when he suggests that if people go to hell, it is because God changes into a "cruel, mean, vicious tormenter;" thus, distorting the view of God and in the process, impugning his holiness. He writes, "Millions have been taught that if they don't believe, if they don't accept in the right way…and they were hit by a car and died later that same day, God would have no choice but to punish them forever in conscious torment in hell. God would, in essence, become a fundamentally different being to them in that moment of death, a different being to them forever. A loving heavenly father who will go to extraordinary lengths to have a relationship with them would, in the blink of an eye, become a cruel, mean, vicious tormenter who would ensure they had no escape from an endless future of agony" (pp. 173-174). The Bible is clear that God, in His love, sent His Son Jesus Christ to die for our sins, so we do not have to end up in a Godless eternity in hell; the fact that some choose to go there does not change the biblical view of God, who is loving and merciful, but also holy and just. Bell goes on to redefine hell again; for him, "Hell is refusing to trust, and refusing to trust is often rooted in a distorted view of God" (p. 175). Bell again fails to see the totality of God's attributes by elevating God's love above God's holiness. He asserts, "We do ourselves great harm when we confuse the very essence of God, which is love, with the very real consequences of rejecting and resisting that love, which creates what we call hell" (p. 177). This chapter shows Bell's myopic view of God, his lack of perspective essentially strips God of some of His key attributes such as justice and holiness.

Chapter 8: The End Is Here

The last chapter is well-written, moving and clear; it beautifully describes Bell's conversion experience. "One night when I was in elementary school, I said a prayer kneeling beside by bed in my room in the farmhouse…With my parents on either side of me, I invited Jesus into my heart. I told God that I believed I was a sinner and that Jesus came to save me; and I wanted to be a Christian. I still remember that prayer. It did something to me. Something in me" (p. 193). Bell affirms, "What happened that night was real" (p. 194). According to this testimony, Rob Bell is a brother in Christ who has accepted Him as Lord and Savior. The implications made in the book regarding God, hell, heaven and the meaning of forever, lead me to believe he is a confused young man who needs to re-evaluate his view of Scripture, his theology and especially his hermeneutics.

I recommend these books on heaven and hell:

Heaven Revealed by Paul Enns

Hell Under Fire by Christopher Morgan and Robert Peterson