Introduction To The Gospels And Acts

Share

This resource is exclusive for PLUS Members

Upgrade now and receive:

- Ad-Free Experience: Enjoy uninterrupted access.

- Exclusive Commentaries: Dive deeper with in-depth insights.

- Advanced Study Tools: Powerful search and comparison features.

- Premium Guides & Articles: Unlock for a more comprehensive study.

INTRODUCTION TO THE GOSPELS AND ACTS

The four evangelists: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. The four evangelists are often symbolized as follows: Matthew (human being), Mark (lion), Luke (ox), and John (eagle).

THE FOURFOLD GOSPEL

The Gospels (in the plural) are more accurately described as the “Fourfold Gospel” (in the singular) according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. This is the way in which the canonical Gospels were viewed by the early church, as is reflected in their ancient titles “The Gospel according to Matthew,” “The Gospel according to Mark,” “The Gospel according to Luke,” and “The Gospel according to John.” This understanding attests to the Gospels’ unity and complementary witness to the one gospel attesting to the life, crucifixion, burial, and resurrection of the Lord Jesus Christ.

The fact that Luke and Acts are separated in the New Testament (NT) canon by the Gospel of John shows that genre considerations overrode keeping Luke-Acts together as a two-volume work. Just as the opening genealogy in Matthew provides a fitting introduction not only to Matthew but to all four Gospels, John’s conclusion furnishes a suitable ending to the entire fourfold Gospel corpus. Matthew’s genealogy presents Jesus as the virgin-born son of Abraham and son of David (Mt 1:1-18); John’s conclusion references the selectivity involved in the task of writing a Gospel (Jn 21:24-25; cp. 20:30-31).

In between these two Gospels, both of which were most likely aimed originally at a predominantly Jewish audience, are two Gospels that are addressed to a predominantly Gentile readership. Mark, most likely writing for a Roman audience, presents Jesus as the “Son of God,” attested by a Roman centurion at the climax of his Gospel (Mk 15:39). Luke—a highly educated Gentile whose literary patron was Theophilus, a Roman government official—drew on eyewitness accounts to highlight the fulfillment of messianic expectations in Jesus and to defend Christianity against charges of political subversiveness.

MATTHEW, MARK, AND LUKE IN RELATION TO EACH OTHER (SYNOPTIC PROBLEM)

The relationship between Matthew, Mark, and Luke is typically called “the Synoptic problem,” but this is entirely too negative a way to cast the issue. Rather than constituting a “problem,” the relationship among these three Gospels is better conceived as an asset. Conceived in this way, the Synoptics provide complementary accounts of Jesus’s life, in keeping with the ancient Jewish belief that the truth of a matter must be established by a minimum of two or three witnesses (Dt 17:6; 19:15; cp. Mt 18:16; Jn 8:17; 2Co 13:1).

Matthew was one of the Twelve and thus witnessed many of the events he recorded. Mark, according to church tradition, relied on the testimony of Peter, the preeminent spokesman and member of the Twelve. Luke candidly acknowledges that he himself was not an eyewitness but drew on the accounts of eyewitnesses in compiling his Gospel (Lk 1:2). He also frequently features two witnesses to a given event (e.g, the two disciples on the road to Emmaus in Lk 24), not to mention the fact that he wrote not one, but two books (the Gospel and Acts). All three accounts are therefore based on eyewitness testimony, in keeping with ancient historiographical practice.

A comparison of Matthew, Mark, and Luke shows that the similarities are too great to be coincidental. As to the exact nature of their literary interdependence, both Matthean and Markan priority (i.e., Matthew or Mark being the first to write their respective Gospel) have been advocated in the history of scholarship. The early church largely supported Matthean priority, while most modern scholars favor Markan priority. However, the reality is almost certainly more complex than mere literary connections; the apostles and others were engaged in regular preaching and teaching, and thus many stories that eventually found their way into the written Gospels would have circulated orally for an extended period of time. While there is most likely some kind of literary interdependence, therefore, the complexity of the issue suggests that the exact nature of the interrelationship between Matthew, Mark, and Luke cannot be determined with a high degree of certainty.

JOHN IN RELATION TO MATTHEW, MARK, AND LUKE (JOHN AND THE SYNOPTICS)

Most likely, John wrote his Gospel last, in the AD 80s or 90s, perhaps a full generation after the other Gospels had been completed. For this reason it is rather striking that his Gospel reads quite differently than the three other canonical Gospels. On the one hand, John leaves out many significant events and teachings found in Matthew, Mark, and Luke. On the other hand, John includes some very important events and teachings not included in these other earlier accounts.

Thus the reader looks in vain in John’s Gospel for teaching portions such as the Sermon on the Mount, the Lord’s Prayer, parables, the end-time Olivet Discourse, or the Great Commission (though John includes his own commissioning account in 20:21-23). John also does not narrate Jesus’s baptism, the transfiguration, demon exorcisms, the institution of the Lord’s Supper, and many other events in Jesus’s ministry.

At the same time, John features Jesus’s extended encounters with characters such as Nicodemus (Jn 3:1-15) and a Samaritan woman (Jn 4:1-42). He also includes accounts of seven striking “signs” of Jesus, namely his turning water into wine at the Cana wedding (Jn 2:1-11), the temple clearing (Jn 2:13-22), healings of a centurion’s son and of a lame man (Jn 4:43-54; 5:1-15), the feeding of the five thousand (Jn 6:1-14), the healing of a man born blind (chap. 9), and the raising of Lazarus (Jn 11:1-44).

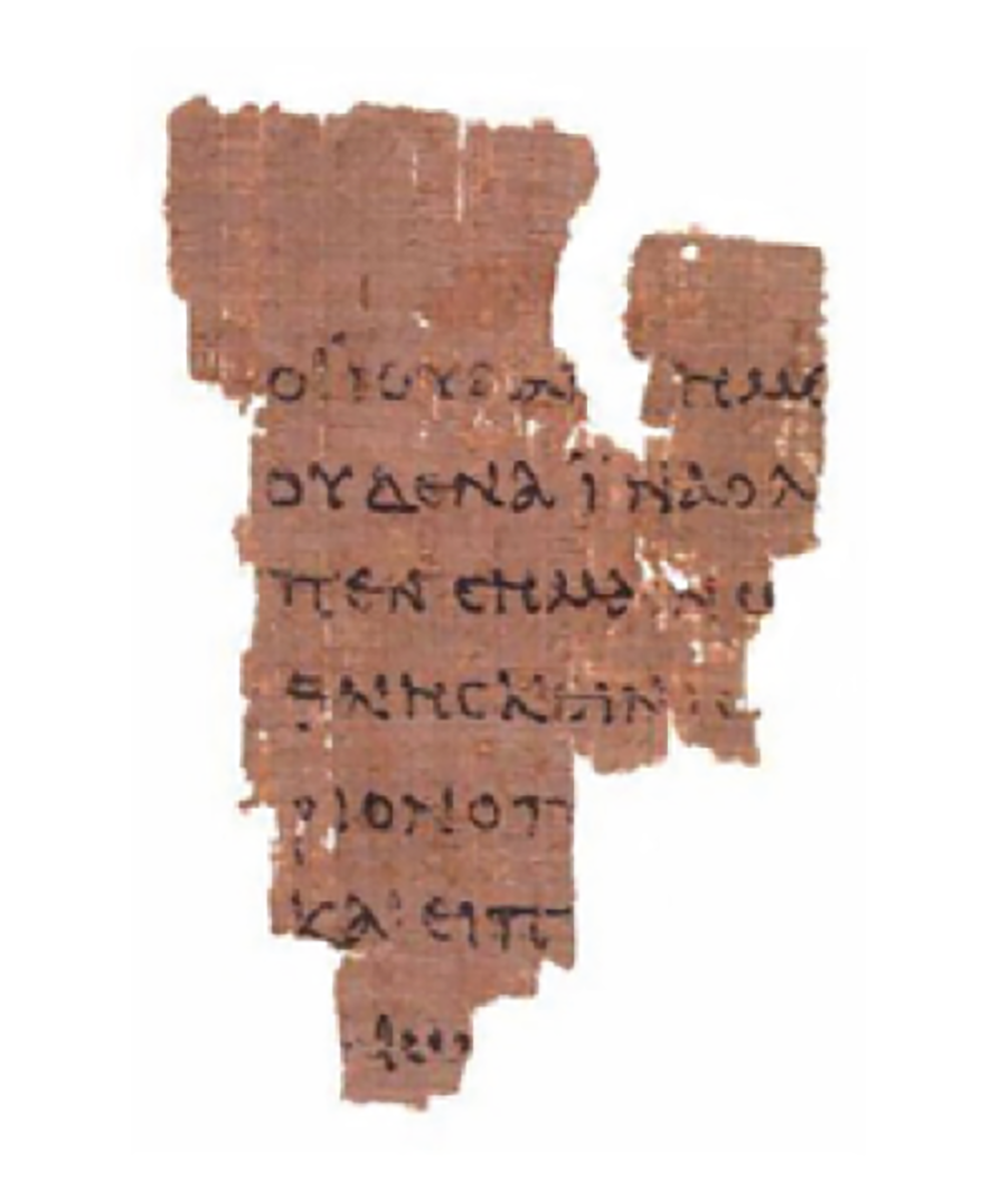

The Rylands Library Papyrus P52 is believed to be the earliest fragment of canonical NT text, dating to between AD 117 and 138. It contains seven lines from the Gospel of John. This fragment, along with a number of others, was acquired on the Egyptian market in 1920 by Bernard Grenfell, an English Egyptologist.

Among the extended teaching portions included in John are the Bread of Life Discourse (chap. 6), the Good Shepherd Discourse (chap. 10), and the Farewell or Upper Room Discourse, which includes the discourse on the Vine and the Branches and Jesus’s high-priestly prayer (chaps. 13-17). In these, Jesus reveals his true nature (often using divine “I am” language) and instructs his followers regarding the coming of the Holy Spirit and their mission subsequent to his departure.

| Important Material Not Included in John | Important Material Included Only in John |

| Teachings | Teachings |

| Sermon on the Mount | Bread of Life Discourse |

| Lord’s Prayer | Good Shepherd Discourse |

| Parables | Farewell or Upper Room Discourse |

| Olivet Discourse | (including Discourse of Vine and Branches and Jesus’s High-Priestly Prayer) |

| Great Commission | |

| Events | Events |

| Jesus’s Baptism | Conversations with Nicodemus, Samaritan Woman |

| Transfiguration | Seven Signs of Jesus: (1) Water into Wine at Cana, |

| Demon Exorcisms | (2) Temple Clearing, (3) Healing of Centurion’s Son, |

| Institution of Lord’s Supper | (4) Healing of Lame Man, (5) Feeding of Five Thousand, |

| Many other events | (6) Healing of Man Born Blind, (7) Raising of Lazarus |

Various proposals have been set forth as to how one should account for these remarkable differences, especially in light of the fact that John in all probability wrote at a time when he would have had access to the preceding Gospels. Some have concluded that the author (perhaps a later community deriving its origin from John) was unaware of the other Gospels and penned a sectarian document. However, this is highly unlikely because the early Christians formed a close network and John almost certainly would have been aware of the existence of the other Gospels and, if so, would have availed himself of them in composing his own account.

More likely is a scenario in which John was aware of at least one of, if not several of, the earlier Gospels, such as Mark, and perhaps even Acts. In such a scenario, rather than following Mark closely (as Matthew and Luke would have done if they used Mark as one of their written sources), John, while drawing indirectly on Mark’s account, may have chosen to tell his story in his own distinct way. It is possible to conceive of this process in terms of “theological transposition,” that is, John taking his point of departure from a given theme or event recounted in Mark or one of the other Gospels and proceeding to reflect on its deeper theological significance.

An example of this kind of theological transposition may be John’s account of Jesus’s miracles. While Matthew, Mark, and Luke speak of these miracles as powerful acts (Gk dynamis), John presents selected acts of Jesus as signs (Gk sÄ“meia), that is, events that highlight aspects of Jesus’s messianic mission. At times, such acts are coupled with “I am” sayings, showing how they display the essence of who Jesus is. For example, the feeding of the five thousand demonstrates that Jesus is the “bread of life” (Jn 6:35); the raising of Lazarus shows that Jesus is the “resurrection and the life” (Jn 11:25).

This makes the profound theological point that people may have witnessed a given miracle of Jesus (the sign) and yet missed the point (its significance): the way in which Jesus’s act pointed to his own nature and identity as the God-sent Messiah. Many other examples could be given: the differing placement of the temple cleansing; showing Jesus’s glory throughout, not merely at the transfiguration; replacing the Olivet Discourse with references to believers’ experience of eternal life already in the here and now; etc.

In fact, John’s theological acumen was recognized by the early church and earned his account the epithet “the spiritual Gospel” (Clement of Alexandria’s term). By “spiritual,” however, these early Fathers did not mean unhistorical; rather, they were struck by John’s unmatched theological profundity. Rather than allowing theological concerns to override historical accuracy, John grounded his theological reflection in historical eyewitness testimony. Reflecting unity in diversity, John and the other three canonical Gospels thus make up the fourfold Gospel, complementing rather than contradicting each other.

THE GOSPEL OF LUKE AND THE BOOK OF ACTS

Luke opens the book of Acts with the statement, “I wrote the first narrative, Theophilus, about all that Jesus began to do and teach until the day he was taken up . . .” (Ac 1:1-2a). By implication, then, Luke conceived of his Gospel and the book of Acts as a coherent two-part narrative, viewing Acts as the sequel to his Gospel that picked up where it left off (i.e., the time following Jesus’s ascension, with minimal overlap; Ac 1:2b-8).

In his Gospel, Luke narrates the fulfillment of messianic prophecy in and through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus (see e.g., Lk 24:26-27,44-47). In the sequel, the book of Acts, Luke narrates the fulfillment of Jesus’s vision that the believing community “will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come on you, and you will be my witnesses . . . to the end of the earth” (Ac 1:8). In this way, Jesus’s mission is shown to be extended through the church’s global, Spirit-empowered witness.

If, then, Luke’s Gospel is a biography, centering on the life of Jesus in continuation of the Old Testament (OT) story (see especially Lk 1-2), what is the genre of Acts? Clearly, both books are historical narrative. If Acts, like the Gospel, has biographical elements, attention is divided between Peter (Ac 1-12) and Paul (Ac 13-28; though see chap. 9). Luke may have conceived of his narrative in Acts as a sort of biography of the Holy Spirit, the ultimate agent standing behind the Acts of the Apostles.

THE INCLUSION OF THE GOSPELS INTO THE CANON

The fourfold Gospel canon has strong early support. The earliest canonical list, the Muratorian Canon (which most likely dates to ca AD 180), includes Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and only these four Gospels. The Church Father Irenaeus, likewise, attests to the fourfold Gospel, contending that it is in the nature of things that there are four Gospels, just as there are four winds and four corners of the earth. Other canonical lists and patristic writers, likewise, reference these, and only these, four Gospels, and the Fathers cite only these as Scripture. Conversely, there is no mention of the Gospel of Thomas or other Gospels in any canonical lists alongside Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

It is therefore far from accurate to say, as some scholars have done, that the four Gospels were selected for inclusion in the canon only in the fourth century AD. While it is true that the canon was formalized and finalized at that time, a “canon consciousness” was present in the church at least by the second century, as canonical lists and patristic citations attest. In fact, of the handful of possible rivals to the Gospels included in the NT none comes even close in terms of date (first century), connection to apostolic eyewitness testimony, and other characteristics. The Gospel of Thomas, for example, is not only late but also constitutes a mere collection of some of Jesus’s alleged sayings, completely lacking any narrative structure. Thus to call Thomas a “Gospel” is really a misnomer.

INTERPRETING THE GOSPELS AND ACTS

The Gospels are properly interpreted as coherent narratives centering on Jesus’s messianic mission culminating in his cross-death and resurrection. Along these lines, each Gospel exhibits a distinctive structure and literary plan as well as particular theological emphases. This unity in diversity results in a fourfold portrait of Jesus that highlights certain aspects of his messianic identity and mission that together provide a rich, full-orbed testimony to this most remarkable individual who came to secure salvation for those who place their trust in him.

Matthew’s Gospel presents Jesus as the son of Abraham and son of David, showing how Jesus fulfilled God’s promises to both Abraham and David. Matthew structures his Gospel around five major discourses of Jesus, beginning with the Sermon on the Mount (chaps. 5-7) and continuing with Jesus’s commissioning discourse (chap. 10), instructions in (kingdom) parables (chaps. 13; 18), and teaching on the end times (chaps. 24-25). These discourse sec-tions oscillate with narrative portions, showing Jesus to be the Messiah in both word and deed.

Mark’s Gospel presents Jesus as the “Son of God” (Mk 1:1) who wields unparalleled authority over nature, sickness, death, and even the evil supernatural (demons). The plot of the Markan narrative pivots on Peter’s confession of Jesus as Messiah halfway through the Gospel (Mk 8:29) and climaxes in the Roman centurion’s confession of Jesus as the “Son of God” (Mk 15:39). Otherwise, mostly demons confess Jesus as the “Son of God” (e.g., Mk 3:11; 5:7), while Jesus’s true identity remains largely veiled even for his closest followers.

Luke’s Gospel follows a similar literary plan as Matthew and Mark, tracing Jesus’s ministry from the early beginnings in Galilee to his later ministry in Judea. The latter is narrated in an extended “travel narrative” that spans ten chapters and builds drama and suspense as Jesus moves inexorably to Jerusalem, the eventual site of his confrontation with the Jewish authorities culminating in his crucifixion (Lk 9:51-19:27). Like Matthew and Mark, Luke tells the story of Jesus’s demise in an extended passion narrative, featuring several distinctive resurrection appearances of the risen Jesus.

John structures his Gospel in four parts. The account is framed by a prologue (Jn 1:1-18) and epilogue (chap. 21). In between, the first half tells the story of Jesus’s mission to the Jews (Jn 1:19-12:50), featuring seven messianic signs of Jesus. Once rejected by his own people (Jn 12:36-50), Jesus turns to the Twelve, the new messianic community (chaps. 13-17). Like the other Gospels, John includes a passion narrative, though focusing on the Roman rather than Jewish phase of Jesus’s trial. The second half of the Gospel (chaps. 13-20) culminates in a commissioning scene and purpose statement.

CONCLUSION

The Gospels and Acts lay an indispensable foundation for the NT canon as a whole. In narrating the life of the earthly Jesus and the continued activity of the exalted Jesus through the Holy Spirit, they build on the OT foundation of messianic predictions, sym-bols, and types. At the same time, the Gospels and Acts themselves lay the foundation for the remain-der of the NT, both the letters of Paul and others and the book of Revelation.

The letters probe the implications of Jesus’s coming and of his vicarious death and resurrection for believers, while Revelation envisions Jesus’s second coming as the victorious, conquering King who brings about the final judgment and the consummation of human history in the new heavens and the new earth. In this way, the Gospels and Acts constitute an integral part of the canon of Scripture and occupy a central location at the very heart of the church’s message of forgiveness and salvation in Jesus Christ.

Andreas J. Köstenberger