Biblical Doctrine: An Overview

Share

This resource is exclusive for PLUS Members

Upgrade now and receive:

- Ad-Free Experience: Enjoy uninterrupted access.

- Exclusive Commentaries: Dive deeper with in-depth insights.

- Advanced Study Tools: Powerful search and comparison features.

- Premium Guides & Articles: Unlock for a more comprehensive study.

These two heresies teach believers to appreciate the importance of the humanity of Christ as well as provide a lesson on theological method. Both of these views bring presuppositions about humanity to the Bible and conform biblical teaching to them, rather than allowing Scripture to dictate everything, including the presuppositions. Evangelical theological method must always allow the teaching of Scripture to shape theological conclusions rather than transform its teaching on the basis of alien assumptions. Countless theological errors have occurred by imposing human ideas on the Bible.

Along with Jesus’ full deity and humanity, the third and fourth necessary affirmations of biblical Christology are that in the incarnation, the divine and human natures remain distinct, and the natures are completely united in one person. The best evidence of these two realities are passages of Scripture where Jesus’ divine glory and human humility are brought together:

For to us a child is born, to us a son is given; and the government shall be upon his shoulder, and his name shall be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace (Isa. 9:6).

“For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is Christ the Lord” (Luke 2:11).

And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth (John 1:14).

. . . concerning his Son, who was descended from David according to the flesh and was declared to be the Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by his resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ our Lord (Rom. 1:3–4).

None of the rulers of this age understood this, for if they had, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory (1 Cor. 2:8).

But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons (Gal. 4:4–5).

These verses present the profound mystery of the eternal, infinite Son of God stepping into time and space and taking on a human nature. There is no greater thought that could ever be pondered than this.

The belief that Jesus is one person with both divine and human natures has great significance for the possibility of fallen people entering into a relationship with God. Christ must be both God and man if he is to mediate between God and man, make atonement for sin, and be a sympathetic high priest:

For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace by the blood of his cross (Col. 1:19–20).

For there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus (1 Tim. 2:5).

Therefore he had to be made like his brothers in every respect, so that he might become a merciful and faithful high priest in the service of God, to make propitiation for the sins of the people (Heb. 2:17).

In his seminal work Why God Became Man, Anselm of Canterbury (c. a.d. 1033–1109) summarized the importance of the two natures of Christ for his atoning work by saying, “It is necessary that the self-same Person who is to make this satisfaction [for humanity’s sins] be perfect God and perfect man, since He cannot make it unless He be really God, and He ought not to make it unless He be really man” (Book II, ch. 7).

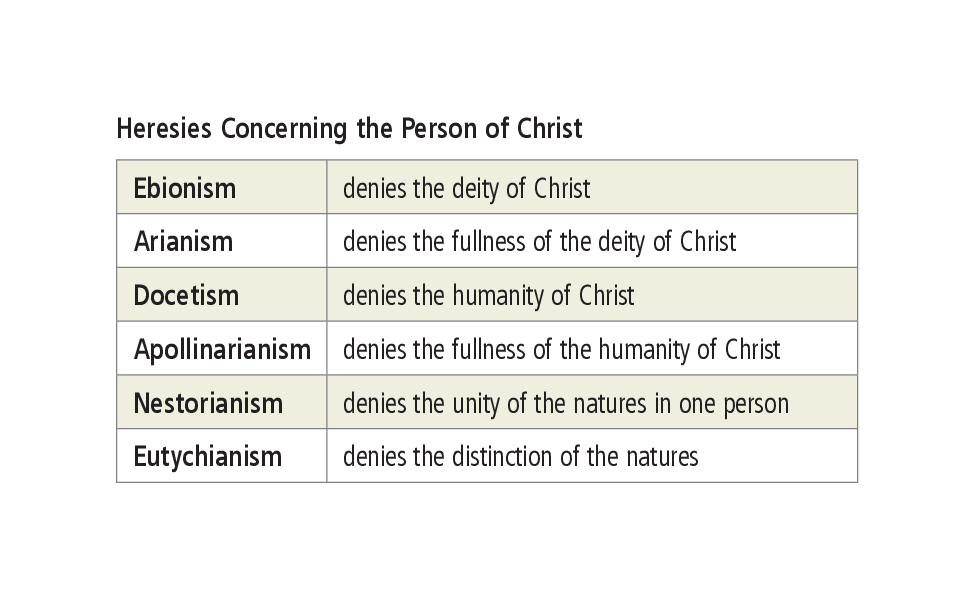

There are six historical heresies related to the person of Christ listed in the chart. The first four heresies are explained above. Nestorianism emphasized the distinction between the natures of Christ so much that Christ was made to appear as two persons in one body. Eutychianism stressed the unity of the natures to the point where any distinction between them was lost, and Christ was thought to be some new entity, with only one nature, greater than mere man while being fully God in a novel way.

In a.d. 451, leaders of the church assembled at Chalcedon (outside of ancient Constantinople) and wrote a creed affirming both Jesus’ full humanity and his full deity, with his two natures united in one person. Hereby all six Christological heresies were rejected. This creed, formulated at Chalcedon, became the church’s foundational statement on Christ. The Chalcedonian Creed reads as follows:

We, then, following the holy Fathers, all with one consent, teach men to confess one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, the same perfect in Godhead and also perfect in manhood; truly God and truly man, of a reasonable soul and body; consubstantial with the Father according to the Godhead, and consubstantial with us according to the Manhood; in all things like unto us, without sin; begotten before all ages of the Father according to the Godhead, and in these latter days, for us and for our salvation, born of the Virgin Mary, the Mother of God, according to the Manhood; one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten, to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably; the distinction of natures being by no means taken away by the union, but rather the property of each nature being preserved, and concurring in one Person and one Subsistence, not parted or divided into two persons, but one and the same Son, and only begotten, God the Word, the Lord Jesus Christ, as the prophets from the beginning have declared concerning him, and the Lord Jesus Christ himself has taught us, and the Creed of the holy Fathers has handed down to us (emphasis added).

The Chalcedonian Creed teaches the church how to talk about the two natures of Christ without falling into error. In particular, Chalcedon teaches the church to affirm that:

1. One nature of Christ is sometimes seen doing things in which his other nature does not share.

2. Anything that either nature does, the person of Christ does. He, God incarnate, is the active agent every time.

3. The incarnation is a matter of Christ’s gaining human attributes, not of his giving up divine attributes. He gave up the glory of divine life (2 Cor. 8:9; Phil. 2:6), but not the possession of divine powers.

4. We must look first to the Gospel accounts of Jesus Christ’s ministry in order to see the incarnation actualized, rather than follow fanciful speculations shaped by erroneous human assumptions.

5. The initiative for the incarnation came from God, not from man.

While this creed does not solve all questions about the mystery of the incarnation, it has been accepted by Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant churches throughout history, and it has never needed any major alteration because it effectively articulates the biblical tension of Christ’s two natures, completely united in one person.

The Holy Spirit is a fully and completely divine person who possesses all of the divine attributes. God the Spirit applies the work of God the Son. The Spirit’s distinct role is to accomplish the unified will of the Father and the Son and to be in personal relationship with both of them.

The Holy Spirit is a distinct personal being with definite characteristics. He is not merely an impersonal force or an emanation of the power of God. (See the article on the Trinity and the discussion of modalism.)

The baptismal formula of Matthew 28:19–20, “baptizing them in [or into] the name [singular; not, names] of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit,” puts the Spirit on an equal plane with the Father and the Son in his deity and personhood (cf. also Matt. 3:13–17; Rom. 8:9; 1 Cor. 12:4–6; 2 Cor. 13:14; Eph. 4:4–6; 1 Pet. 1:2; Rev. 1:4–5).

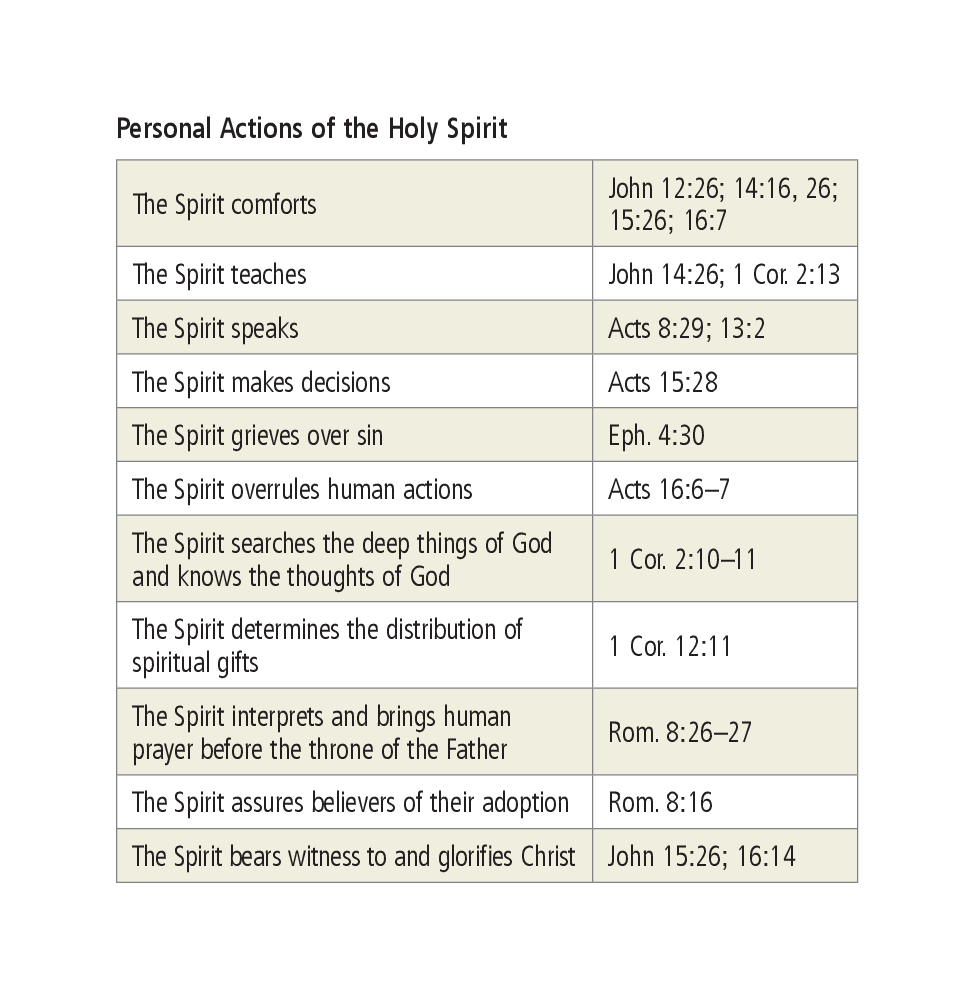

The personal nature of the Holy Spirit is evident in his title “Comforter” or “Helper” (Gk. Parakletos) found in John 12:26; 14:16, 26; 15:26; 16:7. Jesus says he will send the Comforter, who will take his place as his disciples’ helper: “Nevertheless, I tell you the truth: it is to your advantage that I go away, for if I do not go away, the Helper will not come to you. But if I go, I will send him to you” (John 16:7). An impersonal force could never provide as good a comfort as Jesus. The Holy Spirit must be personal in order to fulfill this most personal ministry.

Scripture speaks of several activities of the Spirit (see chart) that can only be performed if he is a personal agent. All of these activities of the Holy Spirit are profoundly personal and interrelate with the Father and Son in a way that could only be through the Spirit’s distinct personal nature.

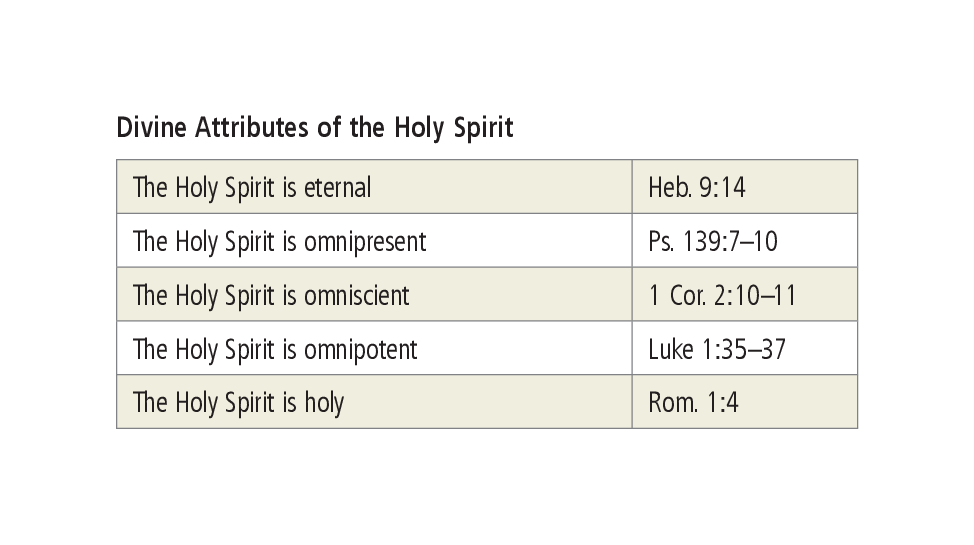

The Holy Spirit possesses all the divine attributes, as shown in the chart. When the Holy Spirit works, it is God who is working. Jesus taught that regeneration is the work of God: “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God” (John 3:5). The divine agent that brings this rebirth is the Spirit: “The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear its sound, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit” (John 3:8). God’s speaking through the prophets is accomplished through the work of the Spirit. As Paul says in Acts 28:25–26, “The Holy Spirit was right in saying to your fathers through Isaiah the prophet: ‘Go to this people, and say, You will indeed hear but never understand, and you will indeed see but never perceive.’” This is a quotation from Isaiah 6:9–10, which is an address from Yahweh to Isaiah. Here in Acts 28:25–26, Paul attributes the words to the Holy Spirit.

Furthermore, the Bible equates a believer’s relationship to the Spirit and his relationship with God. To lie to the Spirit is to lie to God: “But Peter said, ‘Ananias, why has Satan filled your heart to lie to the Holy Spirit and to keep back for yourself part of the proceeds of the land? While it remained unsold, did it not remain your own? And after it was sold, was it not at your disposal? Why is it that you have contrived this deed in your heart? You have not lied to man but to God’” (Acts 5:3–4). The Holy Spirit is the one who guarantees God’s redeeming work in the lives of believers, and he is the one directly grieved by their sin: “Do not grieve the Holy Spirit of God, by whom you were sealed for the day of redemption” (Eph. 4:30).

The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are equal in nature but distinct in role and relationship. The distinct roles typically have the Father willing, the Son accomplishing, and the Spirit applying the work of the Son. The Spirit is clearly at work in the key events throughout the history of salvation, including the creation, Christ’s incarnation, Christ’s resurrection, human regeneration, the inspiration and illumination of Scripture, and the believer’s sanctification.

The Spirit’s role in the human life of the incarnate Christ is often underappreciated. The Spirit brings about the incarnation (Luke 1:35), anoints Jesus for his public ministry at his baptism (Matt. 3:16; Mark 1:10; Luke 3:21–22), fills Jesus (Luke 4:1), leads and empowers Jesus throughout his earthly life (Luke 4:14, 18), and raises Jesus from the dead (Rom. 8:11). The atoning work of Christ is also a Trinitarian accomplishment, with the Spirit playing a prominent role, as seen in Hebrews 9:14: “how much more will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God, purify our conscience from dead works to serve the living God.”

The reality of God’s presence is brought to God’s people by God’s Spirit. His work is central in the promises of new covenant realities. “And it shall come to pass afterward, that I will pour out my Spirit on all flesh; your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, your old men shall dream dreams, and your young men shall see visions” (Joel 2:28); “And I will not hide my face anymore from them, when I pour out my Spirit upon the house of Israel, declares the Lord God” (Ezek. 39:29). These promises are inaugurated at Pentecost when the Spirit’s power is poured out on all nations.

The Spirit is the primary person of the Trinity at work in applying the finished work of Christ in the lives of God’s people. The acts of the Holy Spirit—rather than the acts of the apostles—are the focal point of the book of Acts. He is the one who enables the apostles to accomplish all their kingdom-advancing work. The power of the Spirit is the catalyst of spiritual transformation. Prayer, church attendance, moral living, coming from a Christian family, and knowing all the right religious words are not a sufficient basis for assurance of one’s salvation. But one clear guarantee that someone has passed from death into life is the Spirit’s work transforming that person’s manner of living. He marks the life and character of believers in a definitive way, as seen in Ephesians 1:13: “In him you also, when you heard the word of truth, the gospel of your salvation, and believed in him, were sealed with the promised Holy Spirit” (cf. 2 Cor. 1:21–22).

In the book of Acts, the Spirit’s work was often immediately manifested in miraculous gifts such as speaking in tongues and prophesying. While the Spirit may still choose to work in these ways, it is the fruit of the Spirit that is the normative and necessary evidence of God’s work in someone’s life: “But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control; against such things there is no law” (Gal. 5:22–23). After the inward renewal that makes someone who has trusted Christ a new creation, the Spirit also brings spiritual understanding, convicts of sin, reveals the truth of the Word, brings assurance of salvation, empowers for holy living, teaches, and comforts.

Although the Holy Spirit’s work is evident in the life of someone who is truly born again, even believers can operate “in the flesh” (i.e., by their own self and natural ability apart from God), rather than by Spirit-empowered transformation. God is pleased when his people walk in the Spirit and thus show evidence of his work. God-honoring, unified Christian community is possible only when believers walk in the Spirit. This is why Christians are reminded to “walk in a manner worthy of the calling to which you have been called, with all humility and gentleness, with patience, bearing with one another in love, eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace” (Eph. 4:1–3).

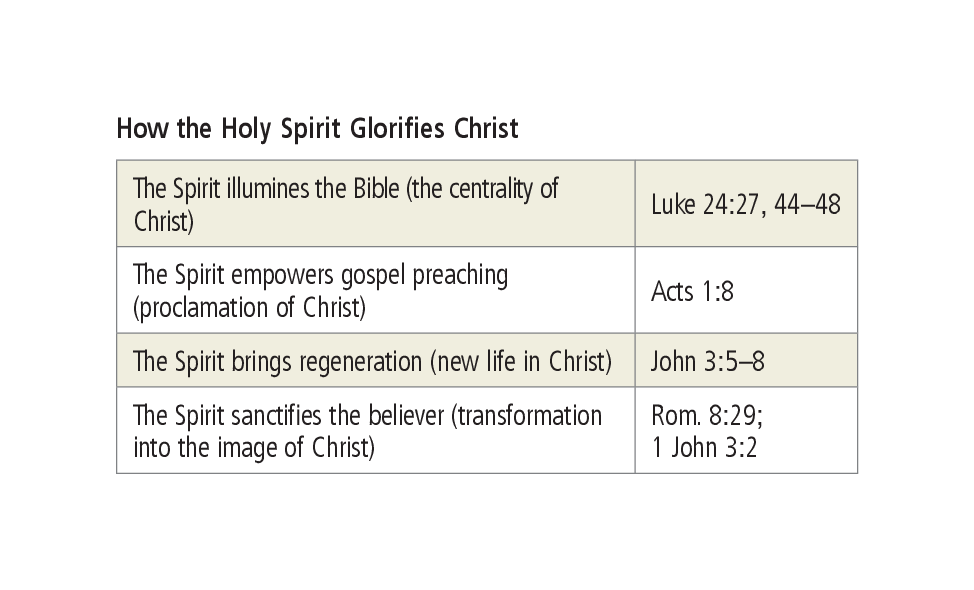

The Holy Spirit’s work can easily be neglected. Perhaps the reason for this is that one of his primary roles is to glorify Christ by testifying to his kingdom and his saving work, past, present, and future: “When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth, for he will not speak on his own authority, but whatever he hears he will speak, and he will declare to you the things that are to come. He will glorify me, for he will take what is mine and declare it to you” (John 16:13–14). Because the Holy Spirit’s purpose is to glorify Christ, he is honored when this objective is accomplished. The Spirit’s deepest longing is that the Son be honored. Jesus is the focus of the Spirit’s ministry, and believers honor the Spirit by depending on his help in order to honor Christ. The Holy Spirit works to advance the work of Christ to the glory of the Father, and he empowers and anoints the people of God to do the same.

As seen in the chart, the Holy Spirit glorifies Christ in four fundamental ways. The Spirit continually points to the beauty and wonder of the Son so that people will be drawn to him, become like him, and point others to him as well: “And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another. For this comes from the Lord who is the Spirit” (2 Cor. 3:18).

Humans become like what they adore. The Spirit works to foster adoration of Christ so that people will become like him. Thus, sanctification flows from adoration, and both are accomplished by the Spirit in the believer’s life.

The ultimate goal of all of life is to know and love God, make him known, and thereby glorify him. This goal is accomplished primarily through the work of the Holy Spirit. Reading the Bible, going to church, Christian fellowship, spiritual disciplines, service, and worship are merely playing at religion if all of these activities are not empowered, guided, and filled by the Spirit. If he is not present, even these good things are fleshly, empty, and repugnant to God: “For if you live according to the flesh you will die, but if by the Spirit you put to death the deeds of the body, you will live” (Rom. 8:13). A life pleasing to God involves daily dependence on the precious Holy Spirit. He is to be known, sought, and loved. His awakening and empowering have always been the essential ingredients of true and lasting works of God in the lives of his people. His work in the transformed lives of believers is the key to a Christian life that experiences God’s blessing and becomes an effective witness to a cynical, skeptical world. Because of the Spirit’s presence, true Christians are no longer slaves to sin: “You, however, are not in the flesh but in the Spirit, if in fact the Spirit of God dwells in you. Anyone who does not have the Spirit of Christ does not belong to him” (Rom. 8:9).

It is often too quickly assumed that Jesus’ holiness and power in ministry were because of his divine nature rather than the work of the Holy Spirit in his human life. As a result, believers may discount Jesus as their true example. In his holy living and powerful ministry, Jesus often drew on the same resources as are available to all believers, especially the leading and empowering of the Holy Spirit.

The three persons of the Trinity have now been fully revealed in redemptive history, and the Holy Spirit is bringing their work to a magnificent consummation. Many believers expect a world revival in the last days that will include all peoples. Even if such a revival does not come in the generation that is now alive, God’s people should be giving glimpses of that coming revival in the character of their lives even today. Such glimpses contribute to fulfilling the Great Commission. Jesus sent his followers even as the Father sent him (John 20:21), and living under and in that authority they are able to say with Jesus, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to preach good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives” (Luke 4:18). When the Spirit works, the gospel will be boldly proclaimed and God’s kingdom will advance.

The doctrine of the work of Christ is traditionally organized by the offices he fulfilled and the stages of his work.

Christ perfectly fulfilled the OT offices of prophet, priest, and king. These offices or roles in the OT reveal aspects of God’s word, presence, and power. The anointing and empowering of the Holy Spirit and favor of God was essential if these offices were to truly represent God. OT prophets, priests, and kings foreshadowed the Messiah who would one day ultimately and definitively be manifest as God’s Son and Word, bringing access to God’s presence and inaugurating the kingdom of God.

A true prophet of God proclaims God’s word to people. God promised Moses that he would raise up a messianic prophet who would authoritatively speak for him: “I will raise up for them a prophet like you from among their brothers. And I will put my words in his mouth, and he shall speak to them all that I command him. And whoever will not listen to my words that he shall speak in my name, I myself will require it of him” (Deut. 18:18–19). Those in Jesus’ day expected the Messiah to fulfill the prophetic role the OT foretold. As the author of Hebrews tells us, Jesus’ prophetic ministry brought all that previous prophets of God had proclaimed to a definitive culmination: “Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world” (Heb. 1:1–2). Jesus equated his own words with the authoritative words of the Hebrew Scriptures, showing that he knew his words were the very words of God. He recognized the unchanging authority of the Mosaic law (Matt. 5:18) and gave his teaching the same weight: “Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words will not pass away” (Matt. 24:35). Because Jesus’ words are the very words of God, they are divinely authoritative, eternal, and unchangeable.

Jesus’ prophetic authority is vastly superior to that of any other prophet because he speaks God’s words as God. The divine authority of his words is based on his identity as God incarnate. He proclaimed God’s truth as the One who is the Truth (John 14:6). His word is the ultimate Word.

Since Jesus Christ is the true and perfect prophet, he is the ultimate source of truth about God, ourselves, the meaning of life, the future, right and wrong, salvation, and heaven and hell. The voice of Jesus in the Word of God should be eagerly sought and obeyed without reservation or delay. Even though Jesus perfectly fulfills the office of prophet, God’s plan is for the church to represent him with its own ongoing prophetic voice, proclaiming truth into the world. Paul certainly saw his own ministry as speaking for God: “Therefore, we are ambassadors for Christ, God making his appeal through us. We implore you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God” (2 Cor. 5:20).

While a prophet speaks God’s words to the people, a priest represents the people before God and represents God before the people. He is a man who stands in the presence of God as a mediator (Heb. 5:1). The priestly work of Christ involves both atonement and intercession.

The atonement is central to God’s work in the history of salvation (1 Cor. 15:4). Atonement is the making of enemies into friends by averting the punishment that their sin would otherwise incur. Sinners in rebellion against God need a representative to offer sacrifice on their behalf if they are to be reconciled to God. Jesus’ righteous life and atoning death on behalf of sinners is the only way for fallen man to be restored into right relationship with a holy God.

Even with the extensive requirements for the priesthood in the OT, there was nevertheless a realization that these human priests were unable to make lasting atonement (Ps. 110:1, 4; cf. Heb. 10:1–4). Jesus alone was able to make an offering sufficient for the eternal forgiveness of sins. Because Jesus was without sin, he was uniquely able to offer sacrifice without needing atonement for himself. In offering himself as the perfect, spotless Lamb of God, he could actually pay for sins in a way that OT sacrifices could not. Jesus’ atoning offering was thus eternal, complete, and once-for-all. No other sacrifice will ever be needed to pay the price for human sin.

Jesus died because of human sin, but also in accordance with God’s plan. The reality of human sin is vividly seen in the envy of the Jewish leaders (Matt. 27:18), Judas’s greed (Matt. 26:14–16), and Pilate’s cowardice (Matt. 27:26). However, Jesus gave his life of his own initiative and courageous love: “I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep. . . . For this reason the Father loves me, because I lay down my life that I may take it up again. No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have authority to lay it down, and I have authority to take it up again. This charge I have received from my Father” (John 10:11, 17–18; cf. Gal. 2:20).

The Father’s divine initiative also led to Jesus’ atoning work: “He who did not spare his own Son but gave him up for us all, how will he not also with him graciously give us all things?” (Rom. 8:32; cf. Isa. 53:6, 10; John 3:16). As in all events of human history, God’s sovereign determination works in a way compatible with human decisions and actions. Even human sin is woven into God’s divine purposes, as is seen in verses that say Jesus was “delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God” (Acts 2:23), and that “Herod and Pontius Pilate, along with the Gentiles and the peoples of Israel” were gathered together to do “whatever [God’s] hand and [God’s] plan had predestined to take place” (Acts 4:27–28).

Christ came to save sinners in order to accomplish God’s will. Christ died in accordance with God’s sovereign, free, gracious choice—not because he was in any way compelled to offer salvation to mankind because of something inherent in us. God did not save fallen angels (2 Pet. 2:4), and he would have been entirely justified in condemning all of fallen humanity to hell; only by reason of his amazing mercy and grace can anyone be saved.

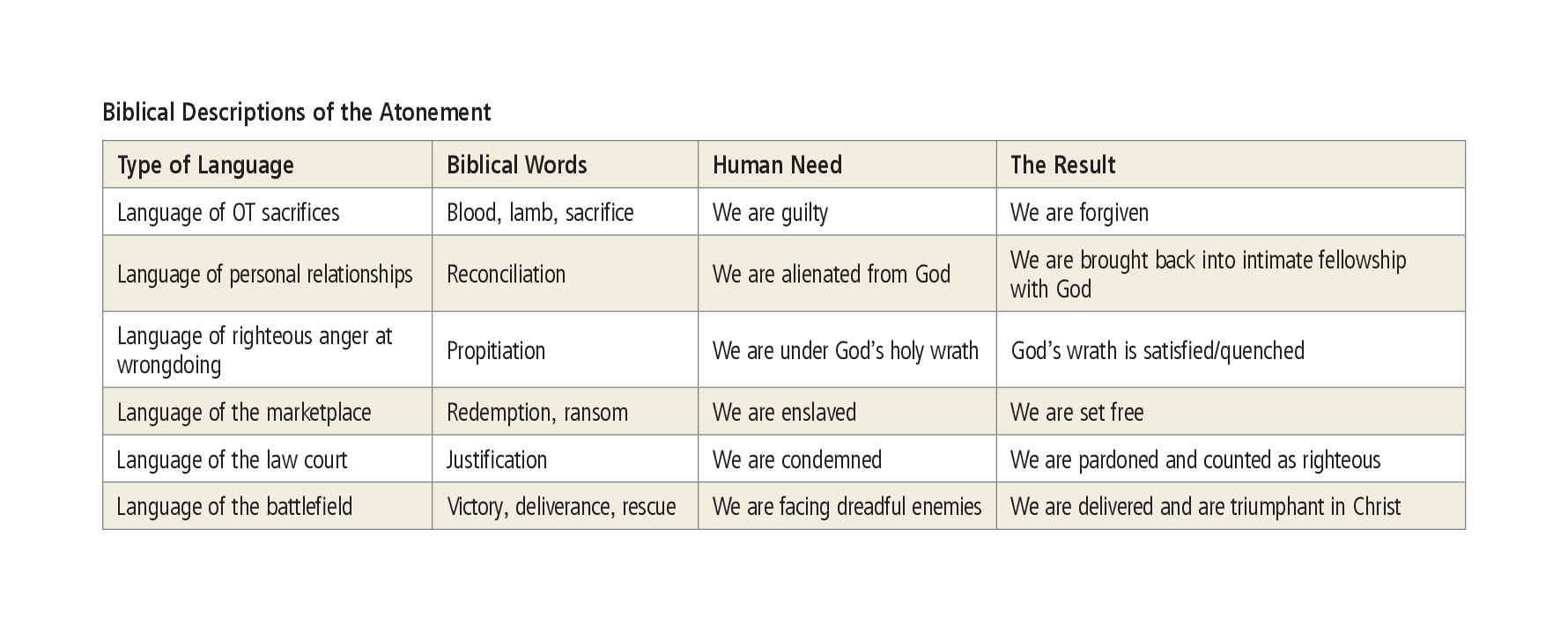

Atonement in the Bible is explained with numerous metaphors and images. The chart shows the varied images the Bible uses to describe the achievement that is at the heart of the gospel.

Throughout church history, various aspects of the atonement have garnered particular attention. For instance, at different times theologians have stressed the ransom imagery, the selfless example of Christ, and the victory of Christ over evil. These aspects of the atonement, rightly understood, contain true and important insights, but the crux of the atonement is Christ taking the place of sinners and enduring the wrath of God as their substitute sacrifice. This is evident in passages like 2 Corinthians 5:21 (“For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God”) and Isaiah 53:4–5 (“Surely he has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows; yet we esteemed him stricken, smitten by God, and afflicted. But he was pierced for our transgressions; he was crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace, and with his wounds we are healed”; cf. Rom. 3:25; Heb. 2:17; 1 John 2:2; 4:10). The fundamental problem of human sin has been solved in Christ’s dying for sinners who deserved eternal judgment. Any attempt to diminish the importance of the penal substitution of Christ for us (i.e., the truth that Christ died to pay the penalty for our sins) will diminish God’s holiness and wrath, as well as the heinous depth of human sin.

Christ’s physical suffering on the cross was outweighed by the emotional, psychological, and spiritual anguish of bearing the sin of mankind and having the wrath of the Father poured out on him. The abandonment and bearing of God’s wrath that Jesus experienced on the cross is beyond our comprehension. On account of this merciful, substitutionary sacrifice he will be worshiped for all eternity by those who are his (Rev. 5:11–12). While Jesus’ death for sinners was the basis of his atoning work, his life of perfect righteousness in their place was also necessary to win their forgiveness. He not only died for rebels, he also lived for them (Rom. 5:19; Phil. 3:9).

Jesus’ priestly work on the cross atoned for sin once for all. Grounded in that atoning work, his priestly work of intercession continues now and forevermore on behalf of his people: “Who is to condemn? Christ Jesus is the one who died—more than that, who was raised—who is at the right hand of God, who indeed is interceding for us” (Rom. 8:34); Christ “is able to save to the uttermost those who draw near to God through him, since he always lives to make intercession for them” (Heb. 7:25). Jesus is alive and always at work representing and bringing requests for believers before the throne of God, intervening in heaven for them. He is the God-man who mediates and represents fallen people based on his fully sufficient work on the cross, and his intervention never fails. Jesus, the sinner’s divine lawyer, never loses a case: “My little children, I am writing these things to you so that you may not sin. But if anyone does sin, we have an advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the righteous” (1 John 2:1).

As the people who constitute the church are intended to have a prophetic voice as Christ’s ambassadors, God also intends to use the church in a priestly role to usher people into his presence. Because of Christ’s work, all of God’s people are viewed as priests with priestly access into his presence and with the privilege of representing people before God (1 Pet. 2:9; Rev. 5:9–10). Prayer, preaching, gospel proclamation, and taking initiative in personal, spiritual ministry are all ways in which God’s people can encourage others to seek and know God and can thereby fulfill their call to represent Christ as a kingdom of priests.

Christ is not only the ultimate prophet and priest, he is also the divine king. Unlike the kings of Israel who were intended to foreshadow the Messiah, Jesus’ reign as messianic King is in no way limited. He rules over all creation and for all time (Luke 1:31–33; Col. 1:17). This rule most directly touches believers at present, but one day all peoples will bow to his royal authority (Phil. 2:9–10). In addition to his comprehensive rule, Christ the King also defends, protects, and shepherds his people and will one day judge all the world’s inhabitants—past, present, and future.

God’s people represent their King when they work to see kingdom realities spread in the world. When they seek social justice—fighting to relieve the plight of the poor, disenfranchised, or unborn—they are working to spread the values of their King. When they work hard and live as good citizens, they are salt and light in a dark world, ultimately serving the interest of their King. One day, when Christ makes all things new, those who are in him will reign with their King: “The saying is trustworthy, for: If we have died with him, we will also live with him; if we endure, we will also reign with him” (2 Tim. 2:11–12a; cf. Rev. 5:9–10).

There is perhaps no more comprehensive yet concise statement on the work of Christ than Philippians 2:5–11:

Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross. Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

These verses teach the profound humility and eventual exaltation of Christ in the history of salvation. The key sequence set out here has been described as the 10 stages of Christ’s work, divided into a humiliation phase and an exaltation phase. The stages are: (1) preincarnate glory; (2) incarnation; (3) earthly life; (4) crucifixion; (5) resurrection; (6) ascension; (7) sitting at God’s right hand; (8) second coming; (9) future reign (some think this will be a millennial reign; see Introduction to Revelation); (10) eternal glory.

The 10 stages and two phases can be visualized as shown in the diagram.

To truly understand the humility of Christ in becoming a man, one must ponder what he gave up in order to make this possible. While we know very little about the experience of God before this world’s creation, we do know that he has always existed as one being, the three persons within his being perfectly relating in mutual love and glorification as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (John 1:1; 17:5, 24). Along with this intra-Trinitarian glorification, angelic beings (creatures themselves) unceasingly worship the infinite worth of the triune God. Jesus consented to surrender this perfect heavenly state so he could represent humanity in his incarnation. When he took the role of a servant and assumed a human nature in addition to his divine nature (Phil. 2:5–11), his divinity was veiled in his humanity. He willingly surrendered the continuous heavenly display and acknowledgment of his glorious divine nature. This amazing humility is taught in 2 Corinthians 8:9: “For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sake he become poor, so that you by his poverty might become rich.” Only when the glories of heaven are finally revealed will what Jesus temporarily gave up in coming to earth as a man be most fully understood. What amazing, loving condescension!

In the incarnation (lit., “in flesh”) Christ took on a full, complete human nature, including a physical body, so that he could truly represent humanity (Phil. 2:6; Heb. 2:17). God the Son chose to come to earth in the most humble way, defying all expectation. His contemporaries saw him as the son of a poor couple, born in a small, obscure village, and with nothing in his appearance to attract them to himself (cf. Isa. 53:2). In the incarnation, God shows in striking manner that he does not value what the world so often values.

Christ’s earthly life was one of continual humiliation. He subtly and selectively revealed his divine glory, even keeping it a secret at times (Matt. 9:30; Mark 1:44; 5:43). He radically altered the prevalent conception of the Messiah, combining the suffering servant of Isaiah 53 with the glorious Conquering King of Daniel 7. Throughout his life Jesus was poor and at times homeless: “Foxes have holes and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head” (Matt. 8:20). His life was one of great and consistent service for the good of others. The last grand gesture of his life before going to the cross was washing his disciples’ feet (John 13:1–17). Although multitudes followed him during his public ministry, he also faced frequent persecution and rejection, at times even in his hometown (Luke 4:28–29). The creatures’ rejection of their Creator epitomizes human rebellion. John 1:10–11 describes this tragedy: “He was in the world, and the world was made through him, yet the world did not know him. He came to his own, and his own people did not receive him.”

Jesus’ earthly life ended with some of his closest friends betraying him (Judas), denying him (Peter), and deserting him (all the disciples, Matt. 26:56). His life was filled with rejection, loneliness, poverty, persecution, hunger, temptation, suffering, and finally death.

Christ’s humiliation reached its greatest depth when he gave his life on a criminal’s cross for sinful humanity. The cross stands at the center of human history as God’s supreme act of love (1 John 4:10, 17) and the only source of redemption for lost and fallen humanity (Rom. 14:9).

While Jesus’ life of humiliation represented the life of human beings living in a fallen world, his victorious exaltation represents a pattern that will someday be reproduced (and is partially reproduced already) in those who believe in him. The exaltation of Christ began when he left his grave clothes in an empty tomb. Sin, Satan, and death were decisively defeated when Jesus rose from the dead. Jesus foretold his resurrection (e.g., Mark 8:31; 9:31; 10:34) and then actually did rise from the dead (as is shown by convincing historical evidence, such as the empty tomb, numerous eyewitness accounts, the radical change in the disciples’ lives, etc.). In addition to defeating sin and death, the resurrection was the Father’s validation of the Son’s ministry (Rom. 1:3) and demonstrates the complete effectiveness of Christ’s atoning work (Rom. 4:25).

First Corinthians 15 provides the most comprehensive treatment of the benefits of the resurrection. By explaining what would be lost if Jesus had not risen from the dead, Paul provides abundant reason for hope in the truth of the resurrection because “in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep” (v. 20). Because Christ rose from the dead, the sins of those who rely on him are forgiven (v. 17), the apostolic preaching is true (v. 15), faith in Christ is true and he can be fully trusted (v. 14), those who follow Christ are to be emulated and their preaching is of great value (v. 19), and those who die in Christ will be raised (v. 18). Because of the resurrection, the Christian has great hope that generates confidence in all circumstances. The resurrection is not merely a doctrine to be affirmed intellectually; it is the resounding affirmation that Jesus reigns over all, and the power that raised him from the dead is the Christian’s power for living the Christian life on earth and the assurance of eternal life in heaven.

The ascension is Christ’s return to heaven from earth (Luke 24:50–51; John 14:2, 12; 16:5, 10, 28; Acts 1:6–11; Eph. 4:8–10; 1 Tim. 3:16; Heb. 4:14; 7:26; 9:24). The incarnation does not cease with Christ’s ascension. Jesus lives, now and forever, as true man and true God to mediate between God and man (1 Tim. 2:5). He will come again as he left, fully God and fully man (Acts 1:11).

Jesus’ ascension is a crucial event in his ministry because it explicitly shows his continual humanity and the permanence of his resurrection. The importance of the ascension is seen in the fact that it is taught in all of the essential creeds of the church, beginning with the Apostles’ Creed. The ascension guarantees that Jesus will always represent humanity before the throne of God as the mediator, intercessor, and advocate for needy humans. Because of the ascension, we can be sure that Jesus’ unique resurrection leads the way for the everlasting resurrection of the redeemed. A human face and nail-scarred hands will greet believers one day in heaven.

Jesus also ascended to prepare a place for his people (John 14:2–3) and to enable the Holy Spirit to come (John 16:7), which he said was more advantageous for the church than if he had stayed on earth (John 14:12, 17).

The current state of Christ’s work is called his “heavenly session,” meaning that he is seated at the right hand of the Father, actively interceding and reigning over his kingdom, awaiting his second coming (Acts 2:3–36; Rom. 8:34; Eph. 1:20–22; Col. 3:1; Heb. 1:3, 13; 8:1; 10:12; 12:2; 1 Pet. 3:22; Rev. 3:21; 22:1). The OT foretold this phase of the Messiah’s work: “The Lord says to my Lord: ‘Sit at my right hand, until I make your enemies your footstool’” (Ps. 110:1). Jesus told of the heavenly session which would precede his return when he referred to the messianic imagery of Daniel 7: “from now on you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power and coming on the clouds of heaven” (Matt. 26:64). The right hand of God is the symbolic place of power, honor, distinction, and prestige. Jesus “sits” to portray the sufficiency of his saving work on earth; he continues a vital, active ministry as he reigns over all creation.

Jesus’ current ministry is a great source of comfort, authority, and encouragement for the believer because it ensures that his ministry as Prophet, Priest, and King continues and will one day be acknowledged by all creation. From his current exalted position Jesus pours out his Spirit on his people: “Being therefore exalted at the right hand of God, and having received from the Father the promise of the Holy Spirit, he has poured out this that you yourselves are seeing and hearing” (Acts 2:33). His precious intercession on behalf of his people takes place at the right hand of the Father so that the believer need never fear condemnation: “Who is to condemn? Christ Jesus is the one who died—more than that, who was raised—who is at the right hand of God, who indeed is interceding for us” (Rom. 8:34).

Biblical interpreters are divided as to whether Jesus’ coming will occur in one stage or two (see the article on Last Things). But all agree that someday Christ will return in great glory and there will be a definitive, comprehensive acknowledgment that he is Lord over all. He will then judge the living and the dead. All people and forces that oppose him will be vanquished, including death itself (Matt. 25:31; 1 Cor. 15:24–28), “so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” (Phil. 2:10–11).

Prior to the incarnation Jesus was glorious. But by displaying his holy character through his incarnate life, death, and resurrection, he received even greater glory. Jesus’ preincarnate glory was taken to a new level when he entered into his eternal glory not only as God but now as God-Man. Jesus displayed his divine character through the human actions of his incarnate life, death, and resurrection. His majesty, mercy, love, holiness, wisdom, and power have been manifested sinlessly in a true man, and for this Jesus will be praised for all eternity. Therefore, the worship of heaven focuses on the work of Christ as the worthy Lamb who was slain:

And they sang a new song, saying, “Worthy are you to take the scroll and to open its seals, for you were slain, and by your blood you ransomed people for God from every tribe and language and people and nation, and you have made them a kingdom and priests to our God, and they shall reign on the earth. . . . Worthy is the Lamb who was slain, to receive power and wealth and wisdom and might and honor and glory and blessing!” (Rev. 5:9–10, 12)

Christ’s eternal glory, which he shares with the Father and the Holy Spirit, is the supreme goal of all that he did. In redeeming a people for himself, he displayed his many perfections in such a way that he will now receive the glory he deserves. That glory will be displayed and acknowledged around his throne, in the songs of heaven forever!

God created human beings and everything else that has ever existed in distinction from himself. From the first verse of the Bible (which declares that God created the heavens and the earth) to the last chapters of the Bible (where God brings about a new heaven and earth), God is seen as the praiseworthy source of all that is. Worship is the right response to God’s creative and sustaining power. Often in the Bible the praise of God’s people arises out of the recognition that God made the heavens and the earth:

“You are the Lord, you alone. You have made heaven, the heaven of heavens, with all their host, the earth and all that is on it, the seas and all that is in them; and you preserve all of them; and the host of heaven worships you” (Neh. 9:6).

Oh come, let us worship and bow down; let us kneel before the Lord, our Maker! (Ps. 95:6; cf. Acts 14:15).

God’s personal, wise power is clearly seen in creation, especially in humanity:

For you formed my inward parts; you knitted me together in my mother’s womb. I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made. Wonderful are your works; my soul knows it very well. My frame was not hidden from you, when I was being made in secret, intricately woven in the depths of the earth (Ps. 139:13–15).

The key passage for understanding the nature of mankind is Genesis 1:26–28:

Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. And God blessed them. And God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth” (Cf. Gen. 2:7; 5:1–2; 9:6; Matt. 19:4; Acts 17:24–25).

Both men and women are made in God’s image (Gen. 1:27), and therefore they are more like God than anything else in all creation. Human beings are intended to live as God’s created analogy for his own glory. God did not create humans because of any need within himself (Job 41:11; Ps. 50:9–12; Acts 17:24–25) but primarily so that he would be glorified in them as they delight in him and reflect his character. We were created primarily to be in relationship with our Creator and find our greatest joy in him. When people are supremely satisfied in him, God is rightly honored and delights in his creation. God describes his people as “everyone who is called by my name, whom I created for my glory, whom I formed and made” (Isa. 43:7; cf. Eph. 1:11–12).

Although God has no unmet needs, humans bring delight to his heart as they trust and obey him.

You shall be a crown of beauty in the hand of the Lord, and a royal diadem in the hand of your God. . . . As the bridegroom rejoices over the bride, so shall your God rejoice over you (Isa. 62:3–5).

The Lord your God is in your midst . . . he will rejoice over you with gladness . . . he will exult over you with loud singing (Zeph. 3:17).

God’s delight in the Spirit-empowered faithfulness of his people is the believer’s greatest motive for holy living in the Christian life. Unbiblical motives for obeying God’s commands include pragmatism, legalism, utilitarianism, and man-centeredness. But biblical ethics insists that our deepest desire should be to find our greatest joy in bringing joy to the heart of our Creator.

When God is recognized as the Creator of everything, he takes his rightful place as the one upon whom we are utterly dependent for all we are and have. Nothing exists apart from the creative and sustaining power of God, and all things owe honor and submission to him. This dependence should lead to deep humility and accountability before the God who made us (Rom. 9:20–21). God’s personal creation of all humans (Ps. 139:13–16) is the basis for human purpose and meaning. The doctrine of creation ensures that we recognize God as majestic and great, and recognize that we are very small before him. When people truly understand God as Creator, they recognize that he is eternal, powerful, wise, good, the owner of all things, and the judge of all. Because God is Creator, all people must answer to him; he, however, need not answer to anyone: “But who are you, O man, to answer back to God? Will what is molded say to its molder, ‘Why have you made me like this?’ Has the potter no right over the clay, to make out of the same lump one vessel for honorable use and another for dishonorable use?” (Rom. 9:20–21).

At the culmination of God’s creation he declared it to be “very good” (Gen. 1:31), but it was later marred and distorted by the fall and God’s curse (Genesis 3; Rom. 8:20–23). Nevertheless, the heavens continue to declare the glory of God (Ps. 19:1–14), God continues to give bountiful gifts to be gratefully enjoyed (1 Tim. 6:17), and God’s image-bearers are encouraged to see and glorify him in all things (1 Cor. 10:31).

The NT compares God’s work of redemption with his work in creation: “For God, who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness,’ has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (2 Cor. 4:6). When God redeems someone, he is re-creating with the same power with which he spoke the world into existence (2 Cor. 5:17; Eph. 2:10). God is the powerful, wise, good God who made everything; knowing this provides great hope for personal and cosmic transformation. There is never room for a believer to despair over his or her own level of sanctification, nor is it legitimate to doubt God’s ability to change someone we are ministering to, because God’s power as Creator is more than able to change rebellious hearts into worshipful ones. We can also be sure that this fallen and cursed world will one day be made new by the One who created it in the first place.

Because God created everything with his glory as the ultimate goal, bringing honor to his name is the appropriate, explicit, overarching objective of all life and ministry: “So, whether you eat or drink, or whatever you do, do all to the glory of God” (1 Cor. 10:31). When planning a worship service or church program, thinking through a business plan, raising a family, creating art, or running a farm, the fundamental question must always be, “Will God be glorified?”

Man is made in the image of God, which means that he is like God and represents God on the earth:

Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them (Gen. 1:26–27).

While everything in creation to some degree reflects something of who God is (Ps. 19:1–6), humans stand alone as made in the image and likeness of God. People are intended to live as God’s created analogies, showing his character more clearly than anything else can show it. Being made in the image of God distinguishes mankind from all other living things.

While humans are the pinnacle of creation, to say we are like God also means that we are not and will never be God. We have great dignity because we are made in God’s image, but our worth is not autonomous. God is the source of all human value.

The fall and curse of humanity distorts the image of God in man but does not remove it from him. After the fall, the image of God remains the basis for human dignity and biblical ethics (Gen. 9:6; James 3:8–9).

The image of God is evident in our unique spiritual, moral, mental, relational, and physical capacities. Humans reflect the image of God in varying degrees and ways, but no one is made in more of God’s image or less of God’s image. The foundation of Christian ethics is the assumption that all humans are made in God’s image regardless of the presence or absence of certain abilities. From conception to death all human beings are God’s image-bearers, and all are creatures of profound dignity and value, equally worthy of protection and respect. The value of human life is not affected or determined by age, disability, race, intellectual ability, emotional or mental state, relational powers, or gender.

The Great Commandment—to love God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength—obviously entails the second greatest commandment: to love our neighbor as ourselves (Matt. 22:37–40). Love for God must be expressed in love for people, even one’s enemies (Luke 6:27). “If anyone says, ‘I love God,’ and hates his brother, he is a liar; for he who does not love his brother whom he has seen cannot love God whom he has not seen. And this commandment we have from him: whoever loves God must also love his brother” (1 John 4:20–21). Christians are called to see beyond mankind’s fallen condition to the image of God in the people they interact with every day, and to love them based on what God says is true of them. This means they no longer regard anyone from a worldly point of view but rather see them with God’s eyes: “From now on, therefore, we regard no one according to the flesh. Even though we once regarded Christ according to the flesh, we regard him thus no longer” (2 Cor. 5:16). As Augustine wrote, “Yet men go out and gaze in astonishment at high mountains, the huge waves of the sea, the broad reaches of rivers, the ocean that encircles the world, or the stars in their courses. But they pay no attention to themselves” (Confessions 10.8).

Jesus, who in his divinity is already the image of the invisible God (2 Cor. 4:4; Col. 1:15), perfectly reflects the divine image in his true humanity and holy life on earth. Jesus shows perfect humanness in his perfect fellowship with and obedience to the Father, which leads to his selfless love for others. These characteristics of Christ’s life are foundational to all other God-glorifying manifestations of the image of God in humanity. Therefore, to experience true humanity, God’s people should pattern their lives after Jesus’ exemplary relationship to God the Father. In this way, they will be conformed more and more to the image of Christ (Rom. 8:29; cf. 1 John 3:2).

Biblically, there are at least two distinct aspects of a human being—spiritual (spirit/soul) and physical (body). Some interpreters hold that the “soul” and “spirit” are distinct parts of a human being, and therefore that we are composed of three parts: body, soul, and spirit. This view is called “trichotomy.” However, the vast majority of evangelical scholars today hold that “spirit” and “soul” are basically synonymous and are two different ways of talking about the immaterial aspect of our being, “soul” pointing to our personal selves as responsible individuals and “spirit” pointing to those same selves as created by and dependent on God. This view is called “dichotomy” (see note on 1 Thess. 5:23–28). It is important to see that there is a fundamental unity between the physical and spiritual within humans. While a distinction is made in the Bible between the material and immaterial parts of the human being, the emphasis is on the necessary connection between body and soul. Regeneration and sanctification for the Christian is a spiritual experience intended to be expressed in the physical body in and through which we have been made to live. The separation of body and soul caused at death is an unnatural tragedy, which will be remedied when the body is resurrected, allowing humans to exist as they were intended to do.

God made man (Hb. ’adam) as male and female from the beginning, completely equal in their value and in their full humanity (Gen. 1:26–27; 9:6), and yet distinct in the way they relate and function. The distinct roles of men and women are grounded in the nature of God (1 Cor. 11:3) and were part of God’s very good creation before the fall (1 Cor. 11:8–10; 1 Tim. 2:13). These role distinctions in no way minimize the worth of men or women. Both are equally made in God’s image, equally fallen (Genesis 3; Rom. 3:23), equally redeemable (Gal. 3:28; 1 Pet. 3:7), and are equally to be resurrected and glorified (1 John 3:2). This equality is expressed, however, with the husband serving in his God-ordained role as authority and servant leader (Gen. 2:23) and with the wife fulfilling her vital role as supporter and helper (Gen. 2:18; 1 Pet. 3:1–6) in the family and the church. Male authority is to be exercised with love, humility, and respect, under the authority of Christ (Eph. 5:25–33; Col. 3:19; 1 Pet. 3:7). Female submission is not servile weakness but rather a display of strength and trust in God as the woman uses all her God-given abilities while refusing to usurp the male authority in her life (Eph. 5:22–25; Col. 3:18; 1 Tim. 2:12; 3:2; Titus 2:4–5; 1 Pet. 3:1–6). The fall greatly distorted the harmonious yet distinct way men and women were intended to function together (Gen. 3:16), and God’s people are called to show the world how men and women are meant to relate in mutually beneficial ways for the glory of God. When men and women function in this complementary way, they display something profoundly and mysteriously like the relationship between Jesus and his Bride, the church. After quoting a verse from Genesis 2:24 that refers to the marriage between Adam and Eve as God originally created it, Paul gives a theological explanation that shows God’s purpose for all marriages, namely, to be a picture of Christ and his church (Eph. 5:32).

God is both transcendent (majestic and holy, far greater than his creatures) and immanent (near and present, fully involved with his creatures). To understand the God of the Bible, this vital biblical tension must be appreciated. God is distinct from and far above all he has made: “The Lord is high above all nations, and his glory above the heavens! Who is like the Lord our God, who is seated on high, who looks far down on the heavens and the earth?” (Ps. 113:4). Yet he is also always actively, personally engaged with his creation: “Yet he is actually not far from each one of us, for ‘In him we live and move and have our being’; as even some of your own poets have said, ‘For we are indeed his offspring’” (Acts 17:27–28). Those most humbled by God’s majesty and holiness most experience personal closeness with him: “For thus says the One who is high and lifted up, who inhabits eternity, whose name is Holy: ‘I dwell in the high and holy place [transcendence], and also with him who is of a contrite and lowly spirit, to revive the spirit of the lowly, and to revive the heart of the contrite [immanence]’” (Isa. 57:15).

Non-Christian religions tend to one extreme or the other; either to a god who is so “other than” creation that nothing meaningful can be said about him (e.g., Eastern and New Age religions) or who is so “identified with” creation that his majestic holiness is lost (e.g., Greco-Roman and much current Western religion). An accurate understanding of God deeply appreciates both his awesome otherness and his intimate nearness. Christians relate to a God who is both the great “I am” and the “God of our Fathers” (Ex. 3:14–15). He is the eternal, infinite God who has stepped not only into time and space but also into covenant relationship with his people through the incarnation of Christ. The biblical balance between God’s transcendence and his immanence is hard to maintain, but the best worship, prayer, and daily relating to God is that which has in it a deep recognition of both God’s majestic holiness and his personal engagement with the creatures he has made.

God is always personally involved with his creation in sustaining and preserving it, and acting within it to bring about his own perfect goals. Everything that takes place is under God’s control. He “works all things according to the purpose of his will” (Eph. 1:11). His providential dominion is over all things (Prov. 16:9; 19:21; James 4:13–15)—like weather (Job 38:22–30), food (Ps. 145:15), and sparrows (Matt. 10:29), as well as kings (Prov. 21:1), kingdoms (Dan. 4:25), and the exact times and places in which people live (Acts 17:26). Salvation is a work of God’s governing power: “For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast” (Eph. 2:8–9; cf. Ezek. 36:24; John 6:37–40; Acts 13:48; 16:14; Rom. 9:16; Phil. 1:29; 2 Pet. 1:1). God’s providential power also brings about sanctification (Phil. 2:12–13) and fruitfulness in ministry (Col. 1:28–29).

God is able to work out his sovereign will within the distinctive characteristics of what he has created. He moves a rock as a rock, and moves a human heart as a human heart. He does not turn a person into a thing when he brings about his sovereign intentions in a person’s life. Paul describes sanctification as the result of both human effort and ultimate divine enabling when he commands believers to “work out your own salvation with fear and trembling, for it is God who works in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure” (Phil. 2:12). He sees no conflict between divine and human activity. Rather, God is uniquely able to bring about his purposes within human beings so that they are fully engaged as persons and responsible for their own decisions, attitudes, and actions.

God controls and uses evil but is never morally blameworthy for it (Ex. 4:11; Deut. 32:39; Isa. 45:7; Amos 3:6). However God’s relationship to evil is understood, both his complete sovereignty and his complete holiness must be maintained. In his great suffering, Job says, “the Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord” (Job 1:21). We are told that Job’s assessment of God’s providence over evil is correct in that “in all this Job did not sin or charge God with wrong” (Job 1:22). Joseph expresses a similar attitude of the God-ordained evil actions of his brothers toward him when he says, “as for you, you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good, to bring it about that many people should be kept alive, as they are today” (Gen. 50:20). The greatest evil ever done, the crucifixion of Christ, happened because of unspeakable human sin, but all within God’s perfect plan. “This Jesus, delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, you crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men” (Acts 2:23; cf. Acts 4:27–28). Even human rebellion unintentionally ends up serving the perfectly wise purposes of God. Nothing—not even sin and great evil—can ever ultimately frustrate God’s sovereignty. Christians can be sure that God will one day defeat all sin, evil, and suffering. Until then, God can be trusted because he is wise, holy, sovereign, and powerful and is always working out his plan to perfection (Rom. 8:28)—even when in the short term it may not seem to be so from our earthly, human perspective.

The Bible explains human rebellion against God from several perspectives and with various images:

“doing . . . evil” (Judg. 2:11)

“disobedience” (Rom. 5:19)

“transgression” (Ex. 23:21; 1 Tim. 2:14)

“iniquity” (Lev. 26:40)

“lawlessness” (Titus 2:14, 1 John 3:4)

“trespass” (Eph. 2:1)

“ungodliness” (1 Pet. 4:18)

“unrighteousness” (1 John 1:9)

“unholy” (1 Tim. 1:9)

“wickedness” (Prov. 11:31)

Sin is anything (whether in thoughts, actions, or attitudes) that does not express or conform to the holy character of God as expressed in his moral law.

1. Sin is moral evil (e.g., murder) as opposed to natural evil (e.g., cancer). Moral evil is personal rebellion against God, and it is what brought natural evil into the world.

2. Sin is always and ultimately related to God. While sin has devastating societal, relational, and physical ramifications, the central problem of sin is that it offends and incurs the wrath of God. David demonstrates this understanding in his confession of adultery and murder: “Against you, you only, have I sinned and done what is evil in your sight, so that you may be justified in your words and blameless in your judgment” (Ps. 51:4). This is not to minimize his sin against Bathsheba, her husband Uriah, or the people of Israel, but rather to recognize that, relatively speaking, it is God he has ultimately offended, and it is to God alone that he must finally answer. Sin is a personal attack on the character and ordinances of God.

3. Sin is breaking God’s law, which can take several forms. There are sins of omission (not doing what we should) as well as sins of commission (doing what we should not do). Breaking one of God’s commandments is rebellion against the entire character of God, and in that sense it is equivalent to breaking all of the commandments: “For whoever keeps the whole law but fails in one point has become accountable for all of it” (James 2:10; cf. Gal. 3:10). God’s unified law is a reflection of his personal nature and claims, which means that rejecting one of his laws amounts to rejecting him.

Although breaking one commandment makes one guilty of breaking God’s entire law, God recognizes that there are gradations of sin. These gradations are based on differences in knowledge (Ezek. 8:6, 13; Matt. 10:15; Luke 12:47–48; John 19:11), intent (Num. 15:30–31), kind, and effect. Nevertheless, even sin done in ignorance is still sin, and everyone still equally needs Jesus to pay the penalty for their sin. While God recognizes degrees of sin on a human, ethical level, it remains the case that all people are equally guilty before God and equally in need of Christ’s atoning work.

4. Sin is rooted deep in our very nature, and sinful actions reveal the condition of a depraved heart within: “Out of the heart come evil thoughts, murder, adultery, sexual immorality, theft, false witness, slander” (Matt. 15:19; cf. Matt. 7:15–19). Internal attitudes are frequently identified as sinful or righteous in the Bible, and God demands not only correct outward actions but also that the heart be right (Ex. 20:17; Heb. 13:5).

5. Sin has brought about a guilty standing before God and a corrupted condition in all humans. The pronouncement of guilt is God’s legal determination that people are in an unrighteous state before him, and the condition of corruption is our polluted state which inclines us toward ungodly behavior. By the grace of God, both this inherited guilt and this inherited moral pollution are atoned for by Christ: “If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness” (1 John 1:9).

Sin entered the human race in the Garden of Eden through an attack of Satan, who led Adam and Eve to doubt God’s word and trust their own ability to discern good and evil (Genesis 3). Sometime prior to this, Satan (a fallen angel) must himself have rebelled against God and become evil, though Scripture does not say much about that event (cf. notes on 2 Pet. 2:4; Jude 6). Satan’s strategy was to bring disorder to the created order by approaching Eve and getting her to lead her husband away from God. Adam, so it appears, allowed his wife to be deceived by failing to take up his God-ordained responsibility to lead and protect her. Satan then questioned God’s goodness, wisdom, and care for Adam and Eve by suggesting that God was a miserly legalist in his prohibition of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Satan then simply lied, saying, “you will not surely die” (Gen. 3:4). Such deception and rebellion against God stem from a failure to trust him and be satisfied with him and his commands and arrangements. Satan and our first parents demanded autonomy and rejected God’s authority, and this has been the source and shape of human sin ever since. Unbelief (Rom. 14:23; Heb. 11:6), pride, and selfishness lead us to think we know better than God and to try to put ourselves in his place. All people, in their fallen condition, are indeed “lovers of self . . . rather than lovers of God” (2 Tim. 3:2, 4).

God rightly judged the rebellion of Adam and Eve and brought a curse on them and all their offspring. The curse brought physical and spiritual death, separation from God, and alienation from him and others. All people are now conceived, born, and live in this fallen, depraved condition: “None is righteous, no, not one; no one understands; no one seeks for God. All have turned aside; together they have become worthless; no one does good, not even one” (Rom. 3:10–12); “All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned every one to his own way; and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all” (Isa. 53:6).

Inherited guilt and corruption leave every person completely unable to save himself or to please God. There are at least six ways this pervasive inability affects everyone. Until God intervenes with his sovereign, gracious, saving power, mankind is totally unable to:

repent or trust Christ (John 6:44; cf. John 3:3; 6:65)

see or enter the kingdom of God (John 3:3)

obey God and thereby glorify him (Rom. 8:6–8)

attain spiritual understanding (1 Cor. 2:14)

live lives pleasing to God (Rom. 14:23; Heb. 11:6)

receive eternal or spiritual life (Eph. 2:1–3)

Because of God’s common grace (that is, his kindly providence whereby sin’s energies within us are partly restrained), total depravity does not mean that every person apart from Christ is as bad as possible. It does mean, however, that none by nature can fulfill man’s primary purpose of glorifying God in relationship with him.

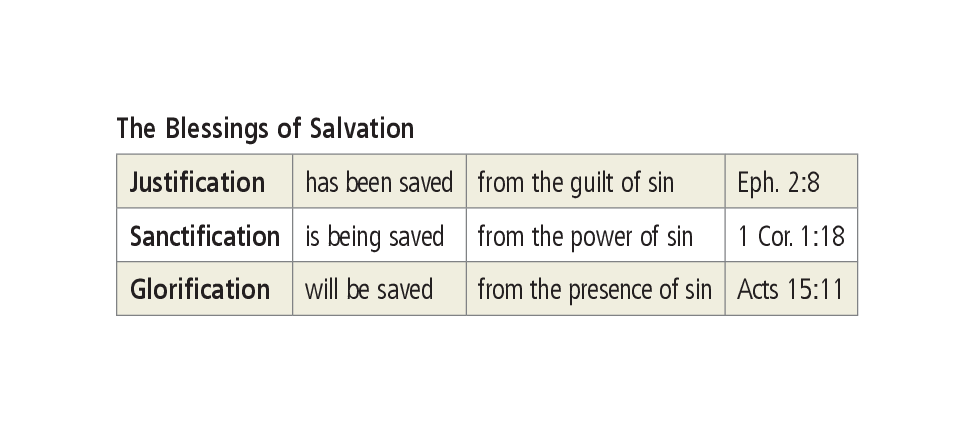

When the Bible speaks of “salvation” (Gk. soteria) in a spiritual sense, the thought can embrace the whole broad range of God’s activity in rescuing people from sin and restoring them to a right relationship with himself. Because of this broad sense, we find that the noun “salvation,” and the verb “save,” are used in the Bible with past, present, and future reference.

Thus, salvation may signify any or all of the blessings outlined in the chart. While the subjective experience of being saved may have degrees and look very different from person to person, the objective state of being saved is categorical and absolute. From God’s perspective there is a definite point in time when those who have trusted in Christ pass from death into life (1 John 3:14). This, however, is not where salvation starts. From God’s vantage point salvation begins with his election of individuals, which is his determination beforehand that his saving purpose will be accomplished in them (John 6:37–39, 44, 64–66; 8:47; 10:26; 15:16; Acts 13:48; 16:14; Romans 9; 1 John 4:19; 5:1). God then in due course brings people to himself by calling them to faith in Christ (Rom. 8:30; 1 Cor. 1:9; 2 Tim. 1:9; 1 Pet. 2:9).

God’s calling produces regeneration, which is the miraculous work of the Holy Spirit in which a spiritually dead person is made alive in Christ (Ezek. 11:19–20; Matt. 19:28; John 3:3, 5, 7; Titus 3:5). The revived heart repents and trusts Christ in saving faith as the only source of justification. To be a Christian means one has traded in his “polluted garment” of self-righteousness for the perfect righteousness of Christ (Phil. 3:8–9; cf. Isa. 64:6). He has ceased striving and now rests in the finished work of Christ—no longer depending on personal accomplishments, religious pedigree, or good works for God’s approval, but only on what Christ has accomplished on his behalf (Phil. 2:8–9). A Christian understands with Paul that “it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me” (Gal. 2:20). As regards Jesus paying the penalty for our sins, the Christian believes that when Jesus said, “it is finished” (John 19:30), it really was. Because of this, “there is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (Rom. 8:1), and they have been “saved to the uttermost” (Heb. 7:25). A miraculous transformation has taken place in which the believer has “passed from death to life” (John 5:24). The Holy Spirit empowers the transformation from rebellious sinner to humble worshiper, leading to “confidence for the day of judgment” (1 John 4:17).

Much of Protestantism in the last two centuries has been influenced by revivalism, which puts a great emphasis on “making a decision for Christ” in a public and definitive way. These “moments of decision” often come to be treated as the crucial evidence that one is truly saved. Other Protestant traditions, less influenced by revivalism, are often content to leave the conversion experience less clearly identified, and put the focus rather on Christian experience, identification with the church, or reliance upon the sacraments. Both of these traditions have benefits and strengths, as well as potential problems. The “decision” approach rightly emphasizes the need for personal commitment to Christ Jesus and the idea that regeneration takes place at a specific time. The potential downside is that this view can lead to a simplistic, human-centered understanding of being saved where one depends too heavily on the initial, specific act of trusting Christ as the primary evidence of conversion. As a result, one can doubt that the “decision” was real, leading to numerous journeys down the aisle (just in case), or else to total dependence on the onetime walk down the aisle, even in the absence of the necessary fruit of salvation. Other traditions appreciate the sovereignty of God and role of the church in the salvation process but can leave conversion so vague that the need for personal trust in Christ and the resulting evidence of a changed life can be neglected.

God uses vastly different circumstances and experiences to bring people to himself. As C. H. Spurgeon said, “God’s Spirit calls men to Jesus in diverse ways. Some are drawn so gently that they scarce know when the drawing began, and others are so suddenly affected that their conversion stands out with noonday clearness.” The best evidence of true salvation is not having raised a hand or prayed a prayer, or having been baptized or christened. Instead, the true test of an authentic work of God in one’s life is sanctification as God continues the moral transformation he began in regeneration. This transformation will continue until the redeemed person is resurrected and made completely holy in heaven (glorification; cf. Rom. 8:28–30; Phil. 1:6; 1 John 3:2).

God’s sanctifying work is seen in growing Christlike character, increasing love for God and people, and the fruit of the Spirit (John 14:2; 15:1–16:33; Gal. 5:22–25; James 2:18). Of course, a memorable conversion experience may serve as an important reference point for a saving work of God in one’s life, but it is only the obvious, ongoing work of the Holy Spirit in making one more and more like Jesus that gives sufficiently clear indication that a person has been made a new creation in Christ. While a Christian should never be satisfied with his current state of holiness, he should be confident that through God’s sovereign, sanctifying grace he will one day have totally won the victory over sin once and for all. This will be the moment of entering by death into a larger life in which our sinful heart is finally purified. Meanwhile, living with this hope as one battles sin daily is true Christian perseverance (1 Cor. 1:8–9; Eph. 1:13–14; 1 Thess. 5:23–24; 1 Pet. 1:4–5; 1 John 2:19; Jude 1, 24–25), which is itself a sign that one has been born again.

The church is the community of God’s redeemed people—all who have truly trusted Christ alone for their salvation. It is created by the Holy Spirit to exalt Jesus Christ as Lord of all. Christ is the Head, Savior, Lord, and King of the church. The relationship between its members results from their common identity as brothers and sisters adopted into God’s family. The identity of this family is grounded in Christ’s person and work and therefore transcends any earthly distinctions of race, class, culture, gender, or nationality. True Christian fellowship is divinely brought about by God, for the purpose of displaying and advancing God’s kingdom on earth. As Christians love one another and submit to the lordship of Christ, they show glimpses of heavenly realities that are to come.

There is ultimately only one church, the global community of believers on earth plus those already in glory. In this world, however, the one church takes the form of countless local churches, each of which must be viewed as a microcosm, outcropping, and sample of the larger whole. Jesus Christ’s headship of the church that is his body is a relationship that applies both to the universal church and to each local church. Denominational identities are secondary to these primary and fundamental realities.

Theologians sometimes distinguish between the “visible church” (the church as Christians on earth see it) and the “invisible church” (the church as God in heaven sees it). This distinction emphasizes two truths. First, only God, who reads hearts, knows the ultimate makeup of the “invisible church”—those whom he has called (“The Lord knows those who are his,” 2 Tim. 2:19). Second, there are some within the “visible church” who are not genuine believers, though they may look as if they are (cf. Matt. 7:15–16; Acts 20:29–30; 1 John 2:19).

The Bible explains the profound mystery of the church (Eph. 5:32) using varied images and illustrations. Among the most important are the church as the building, body, bride, and family of Christ.

Jesus Christ is building his church, and even the gates of hell will not defeat it (Matt. 16:18). He is the foundational cornerstone providing unyielding stability (Matt. 21:42 par.; Acts 4:11; Eph. 2:20; 1 Pet. 2:6–7), and he promises that he will complete the building he is making (Eph. 2:21–22). Therefore, even when the church appears weak, corrupt, and lost, there is always reason for deep confidence in its continued growth and enduring strength. God’s people are “living stones” (1 Pet. 2:5) who have received their life from the Cornerstone, who is the giver of life. The building image is grounded in the temple imagery of the OT, as the place where God’s presence and glory were most often seen. The church is now the place on earth where God primarily dwells and makes himself known. This temple is not made with human hands but exists in the corporate life of those who have been transformed through faith in Christ. The presence and work of God in worship, the ministry of the Word, service to others, discipline, baptism, the Lord’s Supper, and gospel proclamation are now the primary source of the presence and glory of God in the world: “Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you? If anyone destroys God’s temple, God will destroy him. For God’s temple is holy, and you are that temple” (1 Cor. 3:16–17; cf. 2 Cor. 6:16; 1 Pet. 2:4–10). The church will last even beyond the time of Christ’s return, and any predictions that warn of the demise of the church of Jesus Christ are greatly mistaken.

Christ is the head of the church, which is his body (Eph. 1:22–23; 4:15; 5:23). He has authority over his people and determines their direction and destiny. Each member of Christ’s body serves an important and distinct role, and none have life, power, or ability of any kind apart from Christ (1 Corinthians 12).

Christ saves and sanctifies his people through his sacrifice on the cross, which serves as the model of the relationship between a husband and wife (Eph. 5:25). Christ’s self-sacrificial love for his bride continues as he feeds and cares for her; she who will one day be presented to him in spotless perfection (Eph. 5:29; Heb. 12:23). As the bride of Christ, the church should strive for undiluted devotion to Christ, who is her jealous husband (2 Cor. 11:2–4). God’s people should be motivated by and longing for the great wedding banquet as they await the return of their Bridegroom (Rev. 19:7–9; 21:1–4).