The Roman Empire and the Greco-Roman World at the Time of the New Testament

Share

This resource is exclusive for PLUS Members

Upgrade now and receive:

- Ad-Free Experience: Enjoy uninterrupted access.

- Exclusive Commentaries: Dive deeper with in-depth insights.

- Advanced Study Tools: Powerful search and comparison features.

- Premium Guides & Articles: Unlock for a more comprehensive study.

The Roman economy was highly dependent on slavery. Slaves came from conquest in war, voluntary entrance into slavery, or birth into a slave family. There was thus no single racial profile for a slave. The lives of slaves also varied considerably. State-owned slaves who worked in the brutal conditions of the mines had a short life expectancy. Agricultural slaves toiled in the fields. Household slaves served as cooks, hairdressers, servants, and concubines; yet, they could also be trained to positions of significant authority, even administrating businesses for their owners. Such slaves could be granted their freedom, thus achieving the status of “freedmen” and earning the economic benefits of a continued patronage relationship with their former owners. For this reason, some people voluntarily entered into a set period of slavery to wealthy aristocrats (for more on this, see note on 1 Cor. 7:21).

Patronage relationships were central to economic and political life. The wealthy would agree to be the “patron” of certain “clients,” assisting them economically. In return the clients would support their patron by voting for him in his run for political office and by furthering his economic interests. In theory, a chain of patron/client relationships extended from the less prosperous in society all the way up to the emperor, who was the great patron of all Rome.

Citizenship in the NT-era empire was gained by birth to citizen parents, emancipation from slavery to citizens, military service, or special edict. Laws generally prescribed less severe punishments for Roman citizens (see notes on Acts 16:37; 22:22–29), and citizens could appeal their legal cases to Rome (cf. Acts 25:10–12). Despite apparent inequities, a clear legal code, administered through various political officials, is often considered Rome’s great contribution to Western society.

Roman government applied a centralized hierarchy of control, while simultaneously granting some freedom of local self-government. Large cities often retained the right to vote for their leaders, who served in economic, religious, and political civic duties. Some regions (such as much of Palestine in the 1st century) were governed by “client kings,” whose monarchical rule was validated by the emperor. The empire was divided into senatorial and imperial provinces, depending upon whether the Roman senate or the emperor appointed the provincial governors. Generally the more outlying (and less militarily secure) provinces were imperial appointments (such as Syria and the regions throughout Palestine), although the emperors also retained control of some important agricultural regions (esp. Egypt).

Most people in antiquity could not afford an extensive education. Slaves were trained for their specific duties; the poor continued in family agrarian life or were apprenticed to a specific craft. However, education was central to the Hellenistic ideal. Formal education was generally private. Certain slaves, called pedagogues, could be responsible for overseeing the education of their master’s children through hiring teachers (see “guardian” in Gal. 3:24–25). That teacher would educate the children in a set curriculum, including reading and writing, literature, mathematics, Greek and/or Latin, rhetoric, and philosophy. Rhetoric (the study of verbal persuasion) was necessary for political and legal life, and philosophy was considered the highest expression of learning.

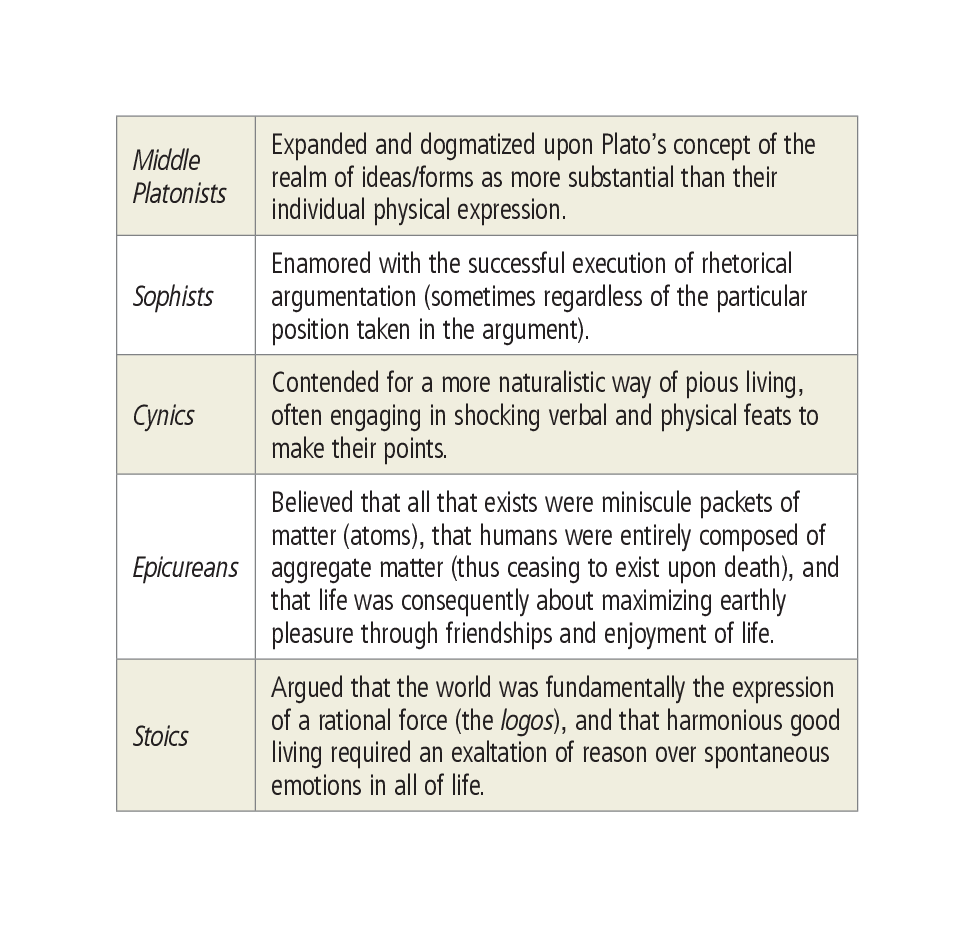

Philosophy involved investigation into the physical and conceptual makeup of the world (metaphysics as well as science) and into ethics. Most religions in antiquity did not substantively address ethical matters (Judaism and Christianity were significant exceptions); rather, this was the realm of philosophy. Various competing philosophical systems were taught around the first century (see chart).

Most today think of Roman religion in terms of its pantheon of gods and goddesses, such as Jupiter, Venus, and Mars (or their Greek counterparts Zeus, Aphrodite, and Ares). Certainly, this pantheon was central to civic life. Touring an ancient city, one would see dozens of temples (some of immense size) dedicated to such deities. These gods were thought to act as benefactors both to the individual and to the city. Yet, should one neglect these deities, they could become angry and injure the individual or society. Thus, the charge of “atheism” against early Christians (who refused to worship such gods) was effectively a concern that rejection of civic gods could lead to widespread catastrophe. Ancient pagan worship assumed a kind of ritual contract where, if specific words were said, and if certain sacrifices or libations were performed, the god/goddess was obligated to respond to benefit the worshiper.

Nevertheless, beyond the great gods of the pantheon, each household also worshiped some of the hundreds of other lesser deities that were thought to rule every aspect of human life. Thus Roman houses typically had at their entrance a shrine, a lararium, where daily libations were poured to these household gods.

Hero worship in antiquity could lead to the elevation of great conquerors as gods. Thus some revered Alexander the Great as a god in his lifetime. Perhaps it was this tendency that allowed the emperor, as patron of the whole empire, to be received as a god, especially in Asia Minor where extravagant temples to the emperors were built even before the NT period. Some emperors (esp. Gaius Caligula, Nero, and Domitian) were known to encourage their own worship.

By the first century a.d. mystery religions had become widespread throughout the empire, conducting secret ceremonies to gods and goddesses of Asian or Egyptian origin. The inductees learned the mysteries and participated in secretive worship practices.

Magic, though often viewed with suspicion, still played a central role in Roman life (e.g., Acts 13:6; 19:13–20). Alongside the worship of gods of healing (such as Asklepies), magic provided healing remedies, as well as promoting potions, incantations, and charms to provide material and physical blessings or curses. The Romans were also concerned with knowing the future through dreams, prophetic oracles, and various forms of divination (i.e., the reading of portents such as animal entrails, astrological signs, etc.; cf. Acts 16:16).

Most people in antiquity were involved in syncretistic worship of multiple deities. Yet some were attracted to monotheistic beliefs, especially those of Judaism and Christianity. Judaism had been granted official legitimacy by Rome, and evidences of Diaspora Jewish communities abound throughout the Mediterranean and Mesopotamia. While some admired Judaism’s worship of a single god and its high ethical ideals, others believed its practices (esp. circumcision, Sabbath, and food laws) to be ridiculous. Christianity was often suspected and persecuted for its “atheistic” beliefs (since it rejected all other gods), its worship of a crucified Lord, its practice of the Lord’s Supper, and its view of all Christians as “brothers and sisters.” Nonetheless, the Christian hope thrived; it was declared a legitimate religion under Constantine in the fourth century and eventually grew to become the dominant faith of people throughout the Roman Empire.