Exodus

Share

This resource is exclusive for PLUS Members

Upgrade now and receive:

- Ad-Free Experience: Enjoy uninterrupted access.

- Exclusive Commentaries: Dive deeper with in-depth insights.

- Advanced Study Tools: Powerful search and comparison features.

- Premium Guides & Articles: Unlock for a more comprehensive study.

Moses in Egypt (4:18-13:16). Moses at last yielded to God and made his way back to Egypt with this message for Pharaoh: "Israel is my firstborn son ... Let my son go, so he may worship me." Along the way Yahweh met Moses and threatened to kill him because he who was about to lead the circumcised people of Israel had failed to circumcise even his own son. Only the quick intervention of Zipporah saved him, for she hastily circumcised her son in obedience to the covenant requirements.

At the edge of the desert Moses met Aaron. Together they entered Egypt to confront the elders of Israel. After Moses had related all that God had said and done, the elders and the people heard with faith and bowed themselves before the Lord.

Pharaoh's question, "Who is the Lord, that I should obey him and let Israel go?" sets the stage for the conflict that dominates the scene through Exodus 15. Before the drama of redemption was over, Pharaoh would "know the Lord" and would yield to His powerful saving presence. But for now Pharaoh intensified the Israelites' sufferings. This led a bitter Moses to accuse Yahweh.

Yahweh renewed His pledge to be with Israel in deliverance, a pledge grounded securely in His very covenant name Yahweh. God commanded Moses to go back to Pharaoh with the promise that the Egyptian monarch would know that there was a higher authority. Moses would seem like God Himself to Pharaoh, and Aaron would be his prophet. By His mighty acts of judgment, God would make Himself known to the Egyptians.

Again and again Moses and Aaron commanded Pharaoh to let God's people leave Egypt to worship. Despite the signs, wonders, and plagues that revealed the mighty presence of the Lord, the king of Egypt would not relent. In round one of the conflict, the rod of Aaron became a serpent that swallowed those of the Egyptian magicians. Three plagues followed. The Nile was turned to blood, the land was filled with frogs, and Egypt was plagued by gnats. Pharaoh's own magicians could duplicate the first two feats, so he was not impressed. Pharaoh did, however, request that Moses and Aaron pray "to the Lord to take the frogs away." Pharaoh was becoming acquainted with Yahweh, the God of Israel. The plague of gnats, the final plague of round one, exceeded the magical powers of the Egyptian magicians and led them to confess, "This is the finger of God."

In round two of the conflict, the plague of flies demonstrated that Yahweh was present in Egypt. In this plague, the grievous disease of the cattle, and the boils, God distinguished between the Egyptians who suffered God's judgment and the Israelites who experienced God's protection.

Round three of the conflict likewise consists of three plagues. Before sending hail, the Lord asserted that He alone is the Lord of history. Yahweh had raised up Pharaoh for the express purpose of demonstrating His mighty power and proclaiming His holy name. Indeed, some of the officials of Pharaoh "feared the word of the Lord," and Pharaoh confessed his sin. Moses' prayer to end the hail demonstrated "that the earth is the Lord's." Pharaoh, however, again hardened his heart. Plagues of locusts and thick darkness followed to no avail.

The fourth and deciding round of the conflict consisted of but one final plague—the death of the firstborn of every family in Egypt. At last Pharaoh permitted Israel to leave Egypt with their flocks and herds. The structure of Exodus 11-13 underscores the abiding theological significance of this final plague. Here narrative language relating once-for-all saving events alternates with instructional language applicable to the ongoing worship of Israel. The Passover celebration, the consecration of the firstborn, and the feast of unleavened bread serve as continuing reminders of what God did to redeem His people. The firstborn of all the families of Israel belonged to the Lord because He had spared them when He had decimated the families of Egypt.

Exodus 1:1-13:16, which focuses on God's powerful, saving presence, builds steadily to its dramatic conclusion—the death of the firstborn of Egypt and Israel's exodus. Exodus 13:17-18:27 likewise focuses on God's presence, which here guides, guards, and protects.

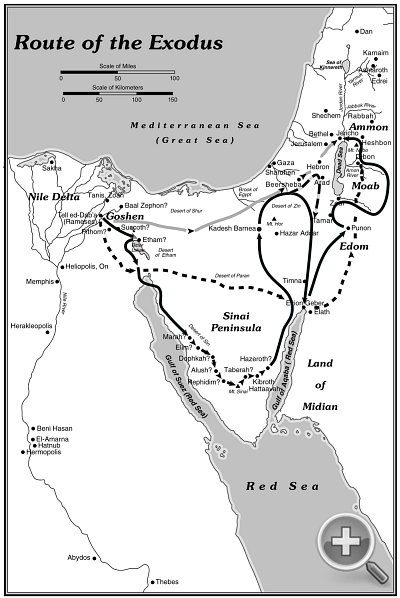

MAP: Route of the Exodus

By means of the pillars of cloud and fire, the Lord guided Israel from Succoth to the wilderness of Etham, just west of the Red (or Reed) Sea. There they appeared to be boxed in by the sea to the east, the deserts to the north and south, and the advancing Egyptian armies to the west. Once more the Lord hardened the heart of Pharaoh so that through his defeat Egypt would know that Yahweh is God. For a tense night the presence of the Lord guarded Israel from the armies of Egypt. Then Yahweh, in the most marvelous redemptive act of Old Testament times, opened up the sea so His people could go safely through while their enemies perished. For generations thereafter Israel commemorated its salvation by singing the triumphant songs of Moses and Miriam, hymns that praised Yahweh as the Sovereign and Savior.

The journey from the Red Sea to Sinai was filled with miracles of provision of water, quail, manna, and water once more. All this occurred despite Israel's complaining insubordination. Hostile and savage desert tribes likewise fell before God's people as He led them triumphantly onward. When heavy administrative burdens threatened to overwhelm Moses, his father-in-law, Jethro, instructed Moses about how the task could be better distributed.

Again and again in the account of the plagues, Moses delivered God's message to Pharaoh: "Let my people go, so that they may worship [or serve] me." At last the moment of worship and service arrived, which the exodus deliverance had made possible. At Sinai Israel was to commit itself to God in covenant. Yahweh based His call to covenant commitment on His mighty acts of deliverance. Only through obedience to God's covenant could Israel fill its role as "a kingdom of priests and a holy nation."

Unanimously they agreed to its terms, so Moses prepared to ascend Mount Sinai to solemnize the arrangement. As Moses was about to go up, Yahweh came down, visiting the mountain with the thunder and lightning of His glorious presence. Moses warned the people to respect the holy (and potentially dangerous) presence of God on the mountain.

As suggested already, the Sinaitic (or Mosaic) covenant is in the form of a sov-ereign-vassal treaty text well attested from the ancient Near East. The treaty established the relationship between the King (God) and His servants (Israel). Its first section is a preamble introducing the Covenant Maker, the Lord Himself. Next a historical prologue outlines the past relationship of the partners and justifies the present covenant. Then follows the division known as the general stipulations, in this case the Decalogue, or Ten Commandments. After a brief narrative interlude, the Book of the Covenant gives the specific stipulations of the treaty.

Contracting parties often sealed their agreement with oaths and a ceremony that included a fellowship meal. The Sinaitic covenant also had its sacrifice, sealing of the oath by blood, and covenant meal. The covenant or treaty texts also had to be prepared in duplicate and preserved in a safe place for regular, periodic reading. Moses therefore brought down from the mountain the tablets of stone to be stored in the ark of the covenant (24:12-18; 25:16).

Once Yahweh and His people Israel had concluded the covenant, arrangements had to be undertaken for the Great King to live and reign among them. Therefore elaborate instructions follow for the building of a tabernacle (or worship tent) and its furnishings and for the clothing and consecration of the priests. The priests, of course, functioned as the covenant mediators. They offered sacrifices on the nation's behalf and presented other forms of tribute to the Great God and King.

The covenant fellowship almost immediately fell on hard times, however. Even before Moses could descend from the mountain with the tables of stone and other covenant texts, the people, with Aaron's consent, violated the covenant terms by casting an idol of gold and bowing down to it. This act of apostasy brought God's judgment and even a threat of annihilation. (See the feature article "Apostasy.") Only Moses' intercession prevented the annulment of the covenant with the larger community.

The Lord was attentive to Moses' cry and did not utterly destroy the idolaters immediately. God did renew His promise to bring His people into the land of promise. Yahweh, however, declared that He could not go with Israel lest He destroy the stubborn, rebellious people. Two narratives stressing God's intimacy with Moses only highlight the Holy One's separation from Israel more. God's people would never make it to the land of promise without God's presence. Twice Moses interceded with God on behalf of rebellious Israel. Yahweh twice revealed Himself to Moses as a God of mercy and compassion. God's mercy and compas-sion—not Israel's faithfulness—formed the basis for renewal of the broken covenant. Descending from the mountain with the tablets of the covenant, Moses appeared before his people, his face aglow with the reflection of the glory of God.

Exodus concludes with Israel's response to God's offer of forgiveness. Without delay the work of tabernacle construction was underway. When it was finally completed, all according to the explicit instruction of the Lord and through the wisdom of His Spirit, the building was filled with the awesome glory of God. By cloud and fire God revealed His presence among the people of Israel whether the tabernacle was at rest or in transit to its final earthly dwelling place in Canaan.

Contemporary Significance. The exodus deliverance is to the Old Testament what the death and resurrection of Christ are to the New Testament—the central, definitive act in which God intervenes to save His people. The Old Testament illustrates how God's acts of redemption call for a response from God's people. The proclamation of God's saving acts in the exodus was the central function of Israel's worship (see Pss. 78:11-55; 105:23-45; 106:7-33; 136:10-16). Christian worship focuses on God's saving act in Christ. (Compare the hymns in Phil. 2:6-11 and Rev. 5:12.) God's saving intervention in the exodus formed the basis both for the prophetic call to obedience (Hos. 13:4) and the announcement of judgment on covenant breakers (Jer. 2:5-9; Hos. 11:1-5; 12:9; Amos 2:10; 3:1-2). Today God's saving act in Christ forms the basis for the call to live a Christlike life (Rom. 6:1-14). God's saving acts in the past gave Israel hope that God would intervene to save in the future (Isa. 11:16; Mic. 7:15). Likewise, God's saving act in Christ is the basis for the Christian's hope (Rom. 8:28-39).

The exodus deliverance, the Sinaitic covenant, the wilderness experience, and the promise of a land provide models of the Christian life. The believer, having already and unconditionally been adopted into the family of God, under-takes his or her own "exodus" from bondage to sin and evil to servanthood under the new covenant. Christians live out their kingdom pilgrimage in the wilderness of this world system, as it were, pressing toward and in anticipation of the eternal land of promise to come.

Ethical Value. God saved and made covenant with His ancient people Israel and demanded of them a lifestyle in keeping with that holy calling. He demands that same adherence to His unchanging standards of all who call themselves His people. The Ten Commandments are an expression of the very character of a holy, faithful, glorious, saving God. Even the "statutes" and "judgments" designed specifically for Old Testament Israel exemplify standards of holiness and integrity that are part and parcel of God's expectations for His people of all ages.

One can also learn a great deal about practical living and relationships by examining carefully the narrative sections. One must be impressed with the faith of godly parents who, in the face of persecution and peril, placed their son in the hands of Yahweh to wait to see how He would spare him. From his birth, then, Moses enjoyed the benefits of a wholesome spiritual environment in the home.

Clearly Moses himself inspires one to a life of dependence and yet dogged determination. Despite his slowness in responding to the call of the Lord in the wilderness, he went on in faith to challenge the political and military structures of the greatest nation on the earth. By the power of his God he overcame the insurmountable and witnessed miraculous intervention over and over again.

Many other examples could be cited, but these are enough to show that Exodus is timeless in its moral and ethical as well as theological relevance.

Cates, Robert L. Exodus. Layman's Bible Book Commentary, vol. 2. Nashville: Broadman, 1979.

Cole, R. Alan. Exodus. Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1973.

Youngblood, Ronald. Exodus. Chicago: Moody, 1983.